The final audio commentary from the out-of-print Twin Peaks – The First Season Special Edition DVD set is from the series Production Designer Richard Hoover. This DVD set was released in December 2001 and contained only the first seven episodes of the series (the pilot was not included). Hoover offers insight about his work designing what show writer Harley Peyton called a “Twin Peaks playground” of sets inside a former machine warehouse turned production studio named City Studios (now Occidental Studios) in Van Nuys, California.

TWIN PEAKS EPISODE 1.007 AUDIO COMMENTARY BY RICHARD HOOVER

The audio commentary from Production Designer Richard Hoover is found under the “Episode Features” tab after selecting “Ep. 7” from the Disc Four DVD Menu.

[Voiceover from Michael J. Anderson plays over the “Previously on Twin Peaks” montage]

The commentary for episode seven explores the set design for the entire series, with production designer Richard Hoover.

[Richard Hoover] I was at the Telluride Film Festival and I saw films, and I was one of them was Twin Peaks and saw the name Mark Frost. Mark Frost is the son of Warren Frost, who was a gentleman. I did some of my first theater with in Minneapolis.

I said, “Wow, this is pretty interesting.” I didn’t know he was. I mean, I knew he had been doing Hill Street [Blues], but I hadn’t really had any contact with him. And I knew him as a kid a little bit, a little bit, you know. And then I called him up and I said, “Mark, I saw your film and I got back to LA, and I loved it. It was bizarre and weird, wonderful.”

And he said, “What are you doing?”

And I said, “Well, I’m about to go.”

“I mean, what are you doing today?”

I said, “Well I….” ”

Well, why don’t you come over and we’ll we’ll talk.”

So I met Mark and Greg Feinberg and then they were in a, a very difficult area because they had to get the sets done. The original designer was not available. They know, and I was I had nothing right there that big. So we just kind of went for it. That’s how it happened. And then it was through the Frost family. That to me was at the beginning, the most primary meaningful moment. And this is like family. You work with people you can continue and that’s good. That’s good. In filmmaking, sometimes, you know, so that’s how that happened.

All generated out of work that had been done up in the Seattle area, Snoqualmie and other towns east and west of Seattle, on the islands and then up inland. So we studied the pilot. We studied the the location photos, and we, you know, learn from what they were. I mean, some of them in a very tactical sense.

What was The Great Northern? What was the Big Pine [ed. note – Richard meant Blue Pine Lodge, home to the Martells and Josie Packard] or whatever, whatever the set happened to be. And we tried to then because then you’re jamming and episodic or jamming scenery into a limited space, even though these were large warehouses and, so then it was like a puzzle, like trying to and not so much character is all. It’s more puzzling. It’s more like fitting it all together.

Part of the, I guess, the magic or of it or the funhouse aspect of it comes from that puzzling in a way, because you have to make it all fit and you have to allow space for operations and space for lighting and space for the story. And so all those elements came together.

So then, then we spent a very rapid week really mapping it out and moving things around and kind of coming up with ground plans and sketches quickly, very quickly, to try to get in to fit them.

And literally at a certain point, you, you move the pieces around like a chessboard and try to get them to wrap, wrap around and that, that for episodic typically or for, a show that’s on a large soundstage, you generally are going through that process as well as the conceptual. You’re kind of both those left and right brain. Things are happening at once, and then you’re budgeting.

And so that’s what we started with. And then everywhere. Then we sort of figured out more about what they’d look like. And then we got into the stories, and then we caught up with the episodes and tried to get Ahold of them, in essence, and figure out what we were doing with them.

In the office, which is really, an office which is, as you learning the cues about the sound, it can sort of, it’s the idea of the psychiatrist transforming the environment. So you relax. So there were two parts. There’s the photograph and then there’s the room.

That’s a real tank. This house happened to have that and we thought it was bizarre and wonderful. And so we just used it.

So a lot of, a lot of the, the art is discovery and, and allowing a location to exist. But in Twin Peaks you really understand the character, the dualities, and you don’t really know where people are on this circuit of madness. Jacoby you don’t know whether he’s crazy or experimenting with psychiatry and trying to really help people. And that’s what, you know, this became a visualization of that.

And it’s much like his his two colors of glasses. He’s got a wacky duality. And you think it’s strange, but he really is, he was really sensitive character, really did care about Laura. And then the fascination with the Hawaiian with the African art and all of that in the wall becomes an extension of that.

And so we would we would really, literally have the conversation and then go, go with it, you know, and try to present the ideas. But the speed of doing this is so fast. You kind of have to get them in there and have the meeting and start working.

The art department creates the entire visual look in concert with the the DP [Director of Photography]. This is straightforward filmmaking in that sense. So all of that is a is part of a collaboration. The director is going to stimulate that collaboration by having strong or various kinds of relationships with the idea.

Then our job is to visualize is to make it come into reality and with the camera department, then to provide ways to light it, to define the details. I mean, you know, inasmuch you could say, when Jacoby’s being knocked out in the. What kind of brush, what kind of where are we? You know, then there’s a certain amount of this that you can control. Some amount of it you’re rushing past, and shapes and lines you try to design. And so there’s a decorating group and a prop group, and construction and paint and those are the instruments of the designer. Those are the that’s the power instruments of the designer, and those are the art director who’s really managing the department.

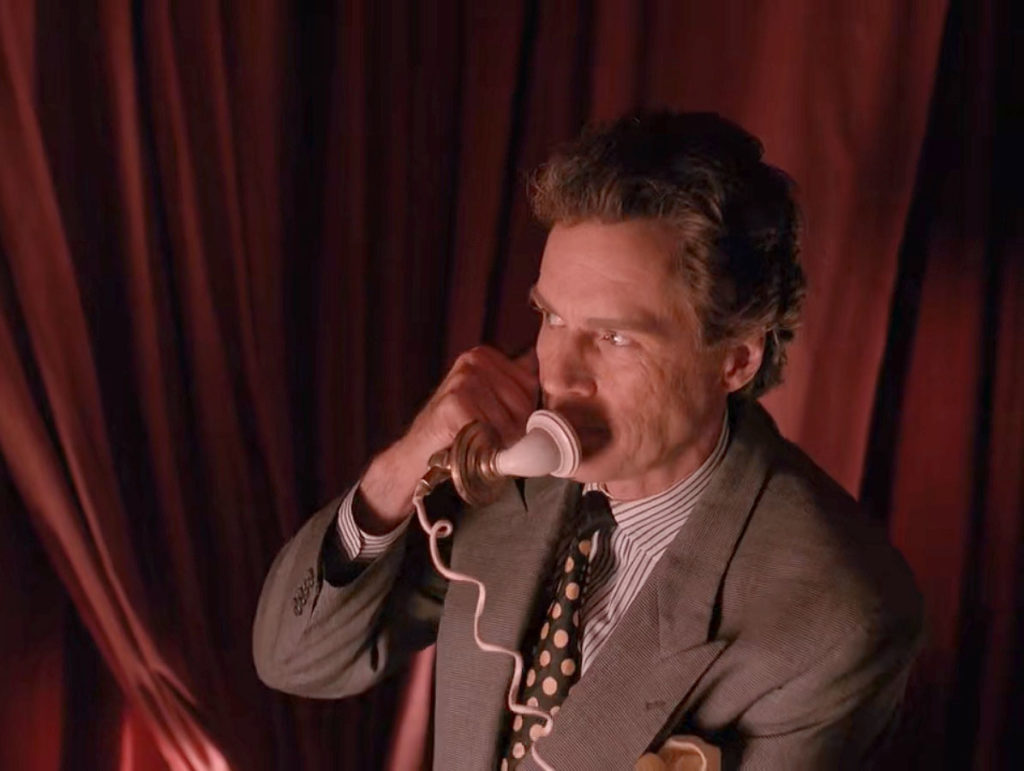

Much of the film is built, but some of it was found. We really went all around L.A. and looking for some interiors. One Eyed Jacks was a house, we found part of it was an interior that had been made out of wood that really fit our theme. And it was, you know, I mean, it’s a, it’s a, a gambling casino across the border, a house of ill repute and, but, it it happened to fit our agenda with the wood and the rock.

And was only really used once. So building that sort of set was, not financially a good idea that I was. But then the office, we had to block, his office we had to build, and that became an octagonal room. So it was really an idea you have you present it and you go for it. And, part again, part of the the magic of discovering these spaces on the soundstage where we were is trying to fit all those elements in.

And what we decided to do was literally have connectivity there be there’d be a room in a hallway always there’d be a ceiling, which is antithetical to a lot of television shooting, at least to that point.

And the connectivity allows the director to provide an entry, like when you’re coming into her office. And so you could literally go from, The Great Northern Lodge [sic] to Blackie’s office in four steps, probably. But the camera can help you get there a little slower. And that’s where that’s why it all was like a warren of hallways, because that’s we ran out of room.

The wonderful thing about the palette is that, the wood being largely reddish and earth tones, we could introduce to into it black and dark colors. And then I think they went through a sweetening a lot. And when they did, when they did their post-production on the tapes, they went and they increased I think you’re seeing a heightened color agenda, which makes the blacks really black, like like Blackie’s dress and the red room you’re in.

So color and in other places became an interest in trying to allow areas of a great solid color. But the color, red is, is the certainly is the is the makes it sexier and also like striking.

Generally the police are, as you can see, are in cooler tones. Obviously Blackie’s being a hot house, it’s hot. The diner had I think it had a red counter. Those ideas came from Lynch and others, you know, when we were starting up where he had really he kind of taught us about color and showed us what he wanted to learn from that. So it’s like it was very interesting because you could do a, a dull, gray world, but this was not a dull, gray world. This is a world of of but you can, darkness and, and and richness really. And and the place where you really also want it to be real.

The designer is as an actor in this space. And you was the director and the cameraman. So we’re all creating an agenda in the mood, temperature, environment, light. All of that is something you decide on. It’s not up in the air. Lighting is the other member of the wedding. I mean, the sense that you really have to think about that.

And of course, locations are always tight and getting grids up are either affordable or they’re not overhead. There’s either room or there’s not. So the first thing, though, for us is to try to find rooms that allow with dressing or windows, implicated sources of light. What is the source of light now?

At One Eyed Jacks, it’s night and the windows are the curtains are closed. You don’t open up to the outside. We’re shooting at day anyway. It helps us some other sets and, you know, might want to see out. So there’s a sense of daylight, but this is something you think about and try to and work with the DP a lot because if it’s not lit, nobody’s gonna see it. It’s a pure principle of physics.

You know, “the secrets in the wood,” the secrets in the the grain of the wood. That something’s inside of that piece of wood. So we decided to use real wood because painting it all would have taken months and months. We didn’t have that much time. And we could get more out of staining and more out of real lumber picking.

Our commitment to it was kind of rigorous. We literally had a we call him the Lumber man, the Log Man from up in Sequoia who would bring regular deliveries of logs, and some of them split and cut up into boards. And we kind of located all the lumber people who had big stock lumber supplies around town and trying to use that lumber and use the real gestalt of that, you know, and get it into the film as opposed to fiberglass or something.

That and I, we felt very strongly about that. I mean, of course we can paint all that in the scenic world, but for me, there was it became a debate of, well, this can be a real log, why are we building in an infrastructure to hold up a fake log when we just get a real log? So we went ahead and did it, foolish as we were.

TWIN PEAKS – EPISODE 1.007 – ACT TWO COMMENTARY

The costume designer is another collaborator. And we definitely don’t go into each set with the wrong color on the actor or the wrong color in the set. It’s it’s part of the dialog. So. And in One Eyed Jacks, it’s kind of silly Victorian prostitute land.

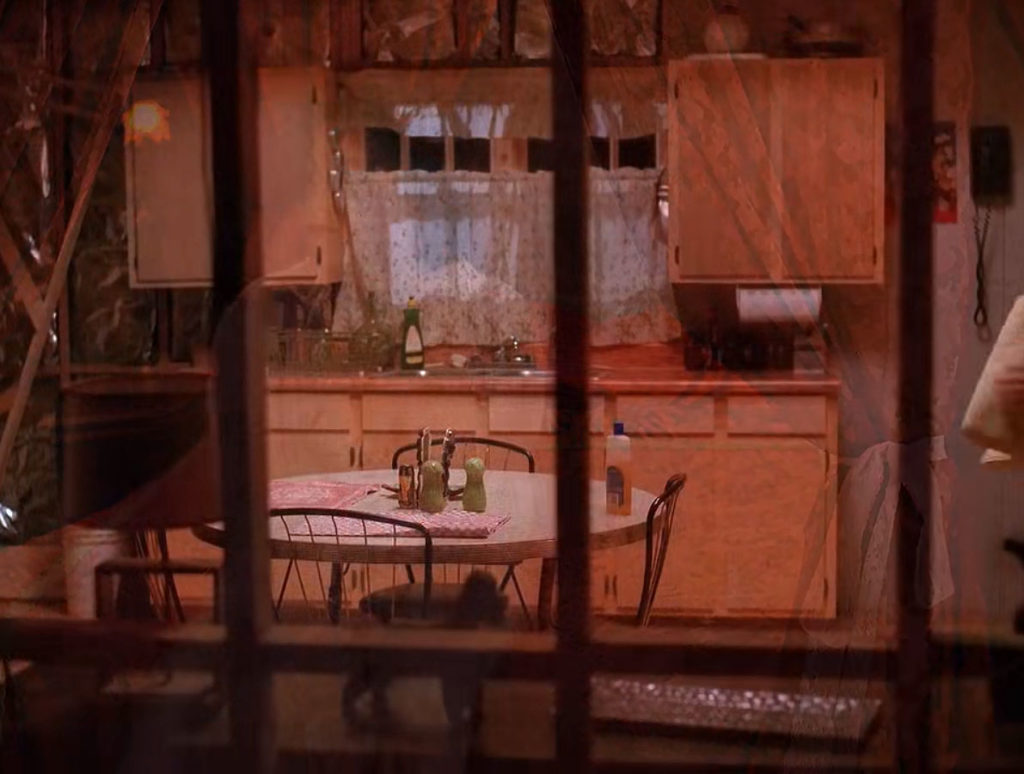

Then we’ve got Mädchen Amick’s house here where it’s working class. And so there’s a different look. All of that’s about character, costumes really start with character, and then what the characters are going through.

Then we try to have our overall concept work inside of that. In this house, this is, Formica counter. So we, you know, it became this let’s pick that. Let’s let’s get the grain in there again, you know. So once the theme is living in our brains, then we try to run with it.

The power plant. This is in Burbank, I think. We’re scouting and there’s a location scout, and then we’re helping them pick that. So it’s really about deciding whether we like the weight and mass. We kind of like these huge, gigantic, scary shapes. And then they we get there, they decide how they’re going to light it. It’s backlit.

And, locations are control and out of control in the sense you decide you like them, it’s an internal decision. I often feel that if you’re on the right location, something’s going on internally, suddenly clicks. If you’re on the right location, it’s fairly clear how to light it. You’re also in a place where you’re not having to reinvent what you’re discovering, because why do that?

We certainly can build this. But, it’s very much part of the work that I like to do. In an episodic, of course, on where you’re shooting seven day episodes, there is prepping, wrapping and shooting going on all at the same time. So it’s often, so you’re really depending on your location scout, which means you’ll get five choices maybe for something.

And we’ll all try to go out and look at it and scout it and block it, but very rapidly. It’s not. It’s less. There’s more time, in that area spent on features then on Twin Peaks. We weren’t doing a Band of Brothers, you know, 25 day shoots.

Doctor Hayward’s house was an attempt to be normal – have the living room, dining room, stairway, kitchen, we didn’t really have a kitchen in it. And yet with some of the colors we picked and some of the wallpapers we picked, which we were trying to let something come out of that, there’s the color yellow that penetrates in the background, occasionally yellow being a color that’s insecure.

It felt insecure in this kind of earthy world. The walls are gray and cool as opposed to being real whites. We just used, a kind of a gray scale as opposed to a, as opposed to any real color. But the yellow accented that and the yellow. And there’s a window that was like, when you get a shot up there, there’s like, what is that window?

It’s something, something churning. And these are, these are latent images. These are latent hidden layers. And sometimes with the objects, you’ll see it in the background on the wall. And it’s it’s the fun part of doing this.

You know, it’s also what, how the DP will light it. This is lit fairly normally. It’s not not too dark. I mean, you got you can see the full figure of the character and, the amount of scenery you’re making, you’re kind of work through all the ideas. What are you going to do here, you know?

So, that’s, I think part of what was going on in our heads. How are we going to make Doc Hayward’s house different now? There’s the there’s a yellow window in the background and an orange light. So I think the agenda here was the lit bits of color lay over a neutral palette as opposed to Blackie’s black, which is red.

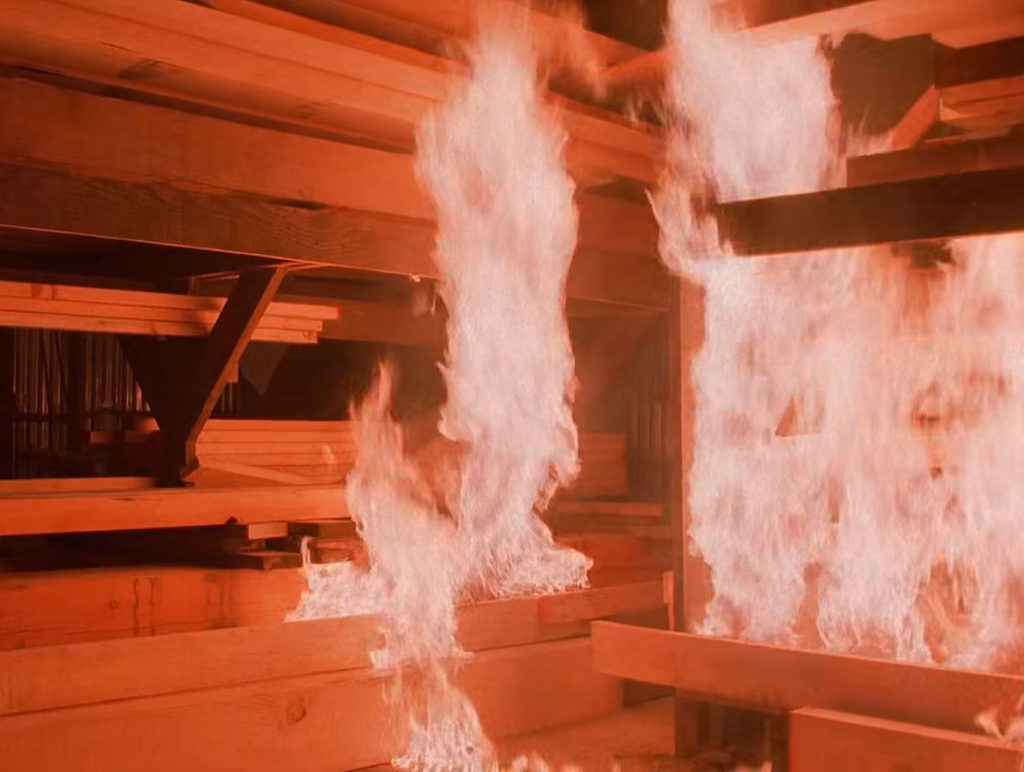

And then the lumber yard was a big effect sequence. We built a shed and then literally had to, because you can’t really burn things in L.A. County very much anymore because of pollution. And so the fire is really cheated, you know, it’s foreground and not much smoke.

This is done up in Valencia. And you keep it away from the forest so it doesn’t start fires. And you, you know, we technically we treated all the wood so it wouldn’t really go get it out of hand. And the fire department was there but it’s a controlled burn. That’s the way you do it.

I had mill pictures, but, we never really went in there. The police station was the headquarters for the lumber yard.

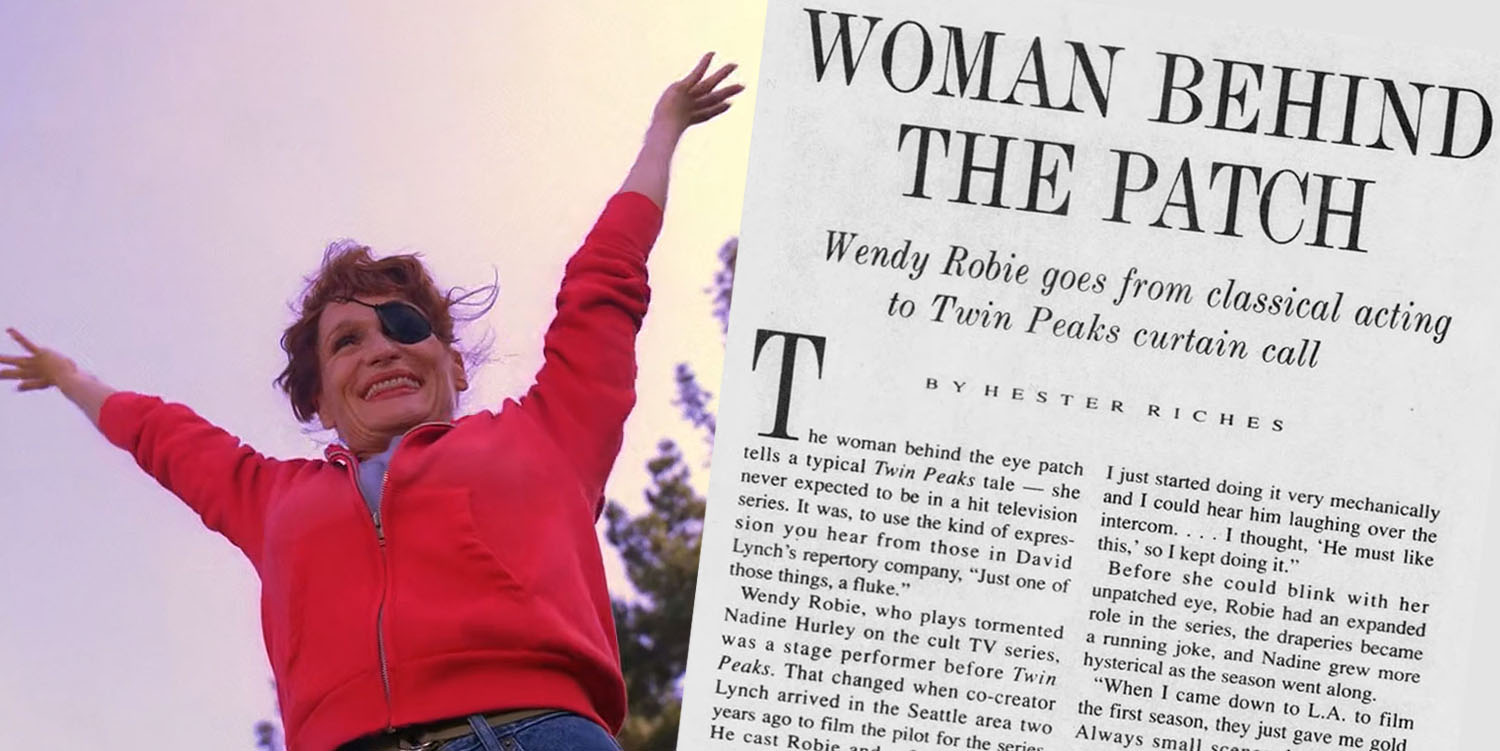

Now this house. Nadine’s house is demanded, because she’s she’s going through a lot of stress in her life, so we decided to sort of take Middle America ranch house and stress it a bit. Now, I don’t think you could see it in these close ups, but, we forced them to have a ceiling. We we kind of got into typical shapes, but we, we wanted them to be a little more demanded.

That’s a split level. It had her shelf with other objects in it, kind of big empty space. It’s kind of the, in a way, an empty house with where the relationship isn’t working. It’s not grungy, per se. We’re not using grunge to say that we’re using emptiness.

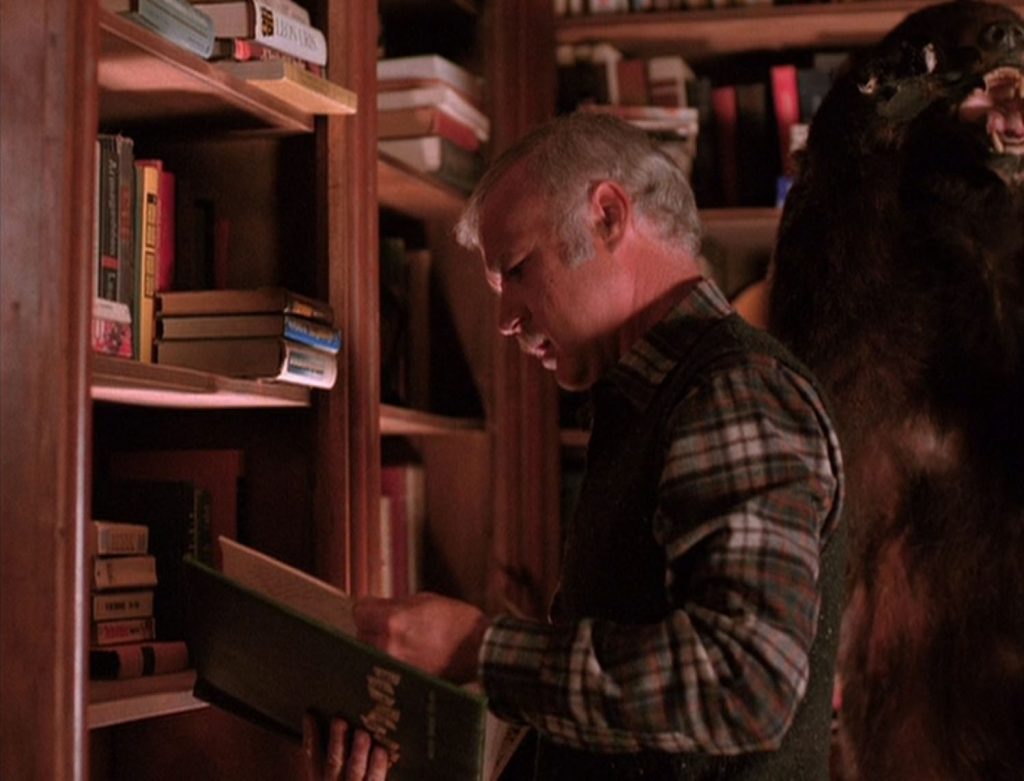

The Big Pine Inn [sic] [ed note. Richard means to say Blue Pine Lodge] in was like all the old family home. The idea, you know, the old lumber mill family. So in as we. I don’t think we ever saw the exterior, but it was, Victorian and just big, rangy, open rooms.

The dressing is filled with energy and life in other words, is also bizarreness that we wanted to get into the into the objects, the life within the object

In The Great Northern, I think you see that in hotels these days where they’re bringing in antiques and things like that, where you’re it’s have our being the focus attention on the antique, on the object, on the artifact. So a lot of artifacts were used and somebody’s pots and pans in the, in the, the big pond.

And again, and you can see in here the we thought to have ceilings and things overhead all the time when a man to compress around these people

It’s the feed house it used to be. It’s the family that’s not there anymore. Sort of, I guess. I’m guessing that’s what we were thinking. The well-being that really isn’t there. I think part of Twin Peaks is plays with versions of homes, as in how people live. What is a hotel? What’s the Big Pine [sic]? What’s what’s the normal home, you know? Like, so this is supposed to be a place where there’s children, there are no children. This is supposed to be, you know, the big, you know, the Ponderosa. This is kind of the the knife in the back of the Ponderosa.

And, of course, then you get the antlers on the wall, which they used and everybody says, wow, what did you think of that? It says, well, we put it there. And then they used it, you know.

Out there in the real world, as we call it, which I think is a suspect question statement. There are all these demented objects. They’re out there, you know, you got the the fun thing was for us to really kind of make the call and the world say, we want to look at your demented furniture and your furniture made from your limbs and from horns. We want to see the chandelier is made from horns and all this kind of is out there. We kind of gathered and built what we could build or went with those themes.

And then again, like, and there’s a shot in there of the big pine with the pot with the bubbles in the pot. Well, that pot exists, but we kind of we like that organic thing kind of what’s bubbling within. So there’s the, the objects are the question, there’s humor and then there’s what’s within, what’s maybe within? So it’s all, on that level. And then there’s the mundane, you know, these are mundane objects, really real. Can you understand what they are? It’s not they they achieve fiction by by how they fit in the harmony of the piece.

TWIN PEAKS – EPISODE 1.007 – ACT THREE COMMENTARY

In this episode, there are more close ups but we prepare the whole. We prepare 360 degrees, unless we’re told or not to have them. You know, that’s really, really up to figuring out what the shots are going to be.

You build the whole set. And the thing is, this is an episode, I think, where there are lots being tied up. There’s there’s multiple stories, and suddenly you really, when you’re close up, you’re really focusing. Now we got it. You know, at the seventh episode, we have desperate people. We have, you know, people cutting their fingers, making blood bonds and, and and, people threatening people.

And it’s all kind of coalescing around up to this, you know, it’s you’ve had some of that, but it’s only been innuendo now. It’s like the rats are out of the the bag.

The directors would come in and this is the week before they would start shooting. And as someone with the script. And then we’d have meetings during the shooting of the script that was going before. So you’re, I have my art director would be handling the the current show. I would be jumping ahead and we’d generally change places and then we’d have to say, well, we need a we need a lumber office. Let’s let’s get it together pretty quickly.

And, and then we’d have draftsmen that would draw it up. But I’d work with the directors and help them. I, you know, first of all, give them the tour and then say, this is where we are, okay? This is what’s in your you need this. We don’t have this. We have to do this. And, we start generating sketches and all that model’s a little bit into our and try to fit it in.

And, the directors each would have their own character characterization approach in a way. And, and this is something you work on for the whole week. It’s, it’s common. It’s what we like to do. It just this happens to be this larger party that they’re joining. So it’s interesting sometimes the, the, it’s an interesting to bring that energy in because like, it’s like bringing someone with a whole new idea into it.

Now the the Twin Peaks police station again was a the exterior was a, I think a lumber mill office, 1950s. And in this case the the wood on the wall we worked on a lot. I think in the second season, we sanded it all down and tried to get the perfect color red. And it was real paneling. Not, not I’m not it was real lumber, not paneling. And that was to get real grain because it’s a lumbering, area.

So the influence of the red, what happens, I think in the video, at least in that period of time when when you we weren’t we weren’t digital. The red starts bleeding a lot. You can kind of see it even in edges of faces. This is this is something we struggled with. I mean, I think they did in the second season trying to figure out how to have the red but have it not totally bleeding. And he’s you see a lot of scenes where there’s the faces are fairly red. They did that and I think in their sweetening. But but we wanted to control it.

A lot of the lighting is is pre-lit. There’s a there’s the demand of the schedule. There’s that aspect to it. It’s, you’re we’re in trouble all the time because we got no time to shoot the scene. So like, in the police station, we had built in light fixtures and we had lids that would come off. And then, then they keep their work on the floor to it to a minimum because that, that slows them down. And I think, I mean, it was a style, but also it’s also very common.

David likes to, he’s he’s a painter. And and he likes to explore time. And that’s and that’s his somewhat his form, is like slowness in the in the piece. Like I found the pieces where he was there, working there. We would spend, more time in certain areas. And Mark’s work was more, like a, like a mystery was like reveal revelation or, the camera is more active in a sense.

But you can see in all of this, you can see like the, the in the hospital scene here, there’s a compositional bleed, like this thing going on between the bodies. And that’s very strange.

And we’re a low angle. We’re not usually you’d might, in a straightforward film, do an over the shoulder. This is an over the elbow shot. So I think pretty much the language that David and and Mark created in the, in the first in the pilot of a compositional language but also a pace was maintain. It’s not a fast pace shooting agenda.

I mean it’s not we’re not doing quick MTV editing or and it’s not a these cameras are on sticks. They’re not floating very much, you know. It’s not Hill Street Blues. So it’s sort of like just getting being kind of very straight with it, let the character come into the frame. And then and then I think a lot of that, I’m guessing a lot of times he’s low, he’s he’s looking at objects to help composition. It’s kind of the ability to look at the for, for a David taught us to really look at the objects and allow us to enjoy those that phenomenon.

So because of David’s fascination with objects and textures, that opened the door to allow us to bring objects in and study objects. So let the camera feast on that. As opposed to skip over it, as opposed to say it was not important.

I’m not here on the environments are environments and the actors, the person on the screen who has to do the day and do the cuts and get through the character. So the feel, the texture of objects, above and beyond what they discussed with us are very important. I mean, there was the I’ve done some black and white films, and it’s sometimes hard to imagine walking on like a green set and having somebody calm down.

But, you know, it’s easier in these environments where it’s real color, and you can touch the real books. And that really does help the actor. It’s really, really quite simple, but it’s something we, we allow when they’re coming on the first day to really have it. Let them live there a little bit.

In the days when they’re doing black and white.They used to paint values of green during the I Love Lucy days, green scale being, a scale that the TV cameras could see easier and get contrast. In other words, you’re seeing black and white on the screen, but you’re the set is really painted in shades of green. It’s fairly sedate. And they also use gray, which is very disturbing to be in, or brown, which is also, to me, very disturbing is like living inside of a doughnut.

But on a colored set, you’ve got the same questions, but you’ve also got the influence, the graphic influence of color and what it happens to do to you psychology.

The Double R Diner – I think everybody complained about it. I mean, we tried to. Really, the diner was based on the real spot, and, so we kind of went with that. We didn’t, we didn’t think clearly enough to say, well, we really need to get tables where people can get around with the camera to do a 360 camera move or whatever. Those were things we in the speed of getting it all built. We didn’t, it didn’t enter our mind.

But then, of course, it’s jammed into a relatively small space, so wilding a wall out, taking a wall away became hard because we had no room. And then that takes a lot of production time up when you take a set apart and put it back together again.

Because a coffee shop is a series of booths or tables or counters. Generally you’re at a booth. Now the booth is a hard object and you have to move everything out of the way. It’s harder. You’re kind of locked into a shape as opposed to a shape that can change, like a big dining room. Probably we should have put for more table, I can’t remember if we had tables in here,

But it was a big set and it was it’s, you know, a diner you kind of were obligated into what that means in a certain sense. What is a diner? What is an American diner? What does it look like? What what is it? What makes it feel typical? What makes it feel acceptable and normal, in which abnormal things happen? But, Oh, I didn’t rebuild it. We just adapted in the second season.

Big Ed’s house is is in many ways a like a wedding cake – it’s a period of time in their relationship that’s frozen. He’s happier at The Book House. He’s happier hanging out with the guys. But at home, which is where he, they fell in love in high school. And this is where it’s been frozen inside the cake.

The wedding cake caught. And that’s what happen with the color and the and the the layer cake and the shelf behind and over behind them there. That’s where she had all of her collection of objects. She’s living in the past, and she’s trapped in her past and her dress, and this fits that as well. You know, we discussed this. This is all talked about. These are themes. These are fun themes.

TWIN PEAKS – EPISODE 1.007 – ACT FOUR COMMENTARY

I think in the dressing, it exists in the 50s, 60s, 70s era and not very much in the 80s. I don’t think specific props were. It sounded like totally in that world. We did not bring it forward. But of course, this is the work in the turn of the century is for mid to late 80s. So, that’s not that long ago, but it wasn’t, you know, computers and film offices were a new and exciting. You want to investigate and we wanted to keep it a bit retro. I think that I think with David’s is fascinated by that. And so we became interested in that.

The Police station is about logic. It’s horizontal lines and logic with with, you know, very strong contrasted colors of a pale blue and the red walls and very institutional. So that’s institutions are about logic. And in this one had it had set in a lumbering area area, therefore with the wood became important.

Hospital this was lit from the top, but it was also lit occasionally like this at night. I think that’s a choice they made. To either accentuate or flatten the drama. This happens to be more dynamic because I think episode seven is where again, we’re lacing it, the mystery is more potent. I mean, it’s coming together and you got all the black coats and shirts and tuxedo.

The style is reality that’s banal, heightened. So you don’t leave reality. You you study it better an answers and you find out what’s partly dark behind it. And so it start with when when the rooms are empty and not dressed. They look like real rooms. When they’re lit and dressed, they become an echo of what you find in the real world.

I mean, in a way you could, what would be fascinating is to shoot this all on location and to go up there and do it and see what you’d learn from that it. Then you’re limited by time of day questions – how you can shoot night for night. Do you want to do that? I think that’s something about Gestalt.

I think the weight of the suggestions are humorous and interesting. There’s also humor in reality. There’s real fear but it’s also a comedy. And Twin Peaks is poking fun at all of that, all of that mystery shooting, fire at the lumber yard which you’ve seen previously.

And the working class guy with the big truck. It uses Western, Mid-Western sensibility, the normalcy of life in which you discover darkness. So you visualize that in a real way. You allow people who are light and people who are dark to live and objects that do the same thing.

I think David Lynch loves exploring the dynamic between darkness and light between individuals and stories, which is to say he is helping us to feast on it, to understand it, to show it. I mean as an artist, it’s inside, I’m sure in his paintings. And I’m going to mention the artist Francis Bacon. In the sense Bacon, when you look at his paintings, they’re beautiful but boy, there is something erupting inside.

And in film, I think this is what David has been exploring in some films. In The Straight Story, a different kind of film, but we know when David was filming Twin Peaks, it was sort of injecting that exploration into the Northwest, basically Middle America. The Northwest represents Middle America, the Midwest. He’s the dark one, he’s the father and we are the children in that regard. In other words, he relishes in that, especially in some episodes he did. He studies it. I think one of the key things is he allows you to look at it.

It’s not a horror movie in the sense that the gooey monster is coming around the corner or you see a shadow of the knife on the wall. But you’re kind of starring at the knife. And as you’re starring, the person is not technically morphing in front of you but you know there is something happening inside and it’s, that’s more about looking at psychosis. What is reality then?

And so that’s a fascinating film genre but the audience is, “Isn’t this real or, no, that’s not real? What am I experiencing?” Well then you’re experiencing part of yourself. Human beings have all of that and certainly what we’ve been through shows that. And again, when I started I talked about the darkness within, the potential there for darkness. And it’s still, he’s fascinated by the potential. Not saying, it is what it is. Trying to keep the tension the whole story. Who is good or bad?

So it effects on how we try to articulate colors into the sets. It affects us in terms of our knowledge of the mundane. What’s real? Because you’re really dancing in both worlds. You’re have, in a kind of Shakespearian sense, you have very normal scenes and very abnormal scenes. And actually it got more and more abnormal in the second season, I mean more strange environments.

But the monster is not living in a cave with dark shadows. The monster is living in the diner, among the doughnuts, in the wood grain. So you are really are allowed to study a phenomenon of acceptable real objects, and then to layer over that, strange color agendas, the influence of red, discover what wood grain can do for you, simplicity of shapes, straightforward graphics. Should be erupting into a huge fire but we could never do that.

Oh the wacko cano … I think we went crazy and just got them. I don’t know. We had torchieres. We wanted it to be Victorian mixed with North woods. Drapery also comes from the zig zag room world, which when you saw later in part 2, you know the dream world, the Red Room.

One Eyed Jacks is like a card, the duality again of characters. It’s like take a chance and she took a chance. Oh God, I love this with the hunchback, I forgot about that. It comes from the Grimm’s fairytale that’s what it is, with a little back doorway.

Uh oh, Dad. This is stuff that, actually when you’re doing it, you didn’t know you were doing it, you know. But it’s good to think of now because we grow. You learn more. I think one of the things about filming is that you learn more. Thank God, as you do it. It’s interesting to reflect on it. I’ve been talking to a lot of people about Twin Peaks for some reason in Europe and stuff. It’s interesting.

I was just doing a play in Denmark and [Twin Peaks] had an effect there and in Japan in ways that it had here but not in the same way. So it becomes an icon of America in that way, but you don’t really know that. It’s not like the paparazzi are following me around, thank God. But with filmmakers and interested in film, it’s fun to talk about it. And actually, they helped me discover what we were doing in a way, get some feedback.

Now, I know more, I’m really trying to think about stories and much more detail I personally learned about on Twin Peaks. You have to engage the storytelling and that’s the delight of it. I learned that simple shapes can gain graphic power. I learned that moving quickly sometimes is an asset through making scenery that, in a way, going with your instinct, that’s what I mean. It means you have an idea. I think anybody would have an idea if you said, “Okay, design a diner or something like that.”

And I kind of cut my teeth on design for film on Twin Peaks in a sense of color and then allowing an agenda like that and then allowing a team of people to go forward with that agenda.

So Twin Peaks is where I started to grow up as a designer. I would say that if you’re a student of design, get that job and do it. Go through that in a year and a half and it’s better than going to college because now you’re like dealing with real building, real design questions. For me it was a gift

[Voiceover by Michael J. Anderson]

Commentaries produced by Three Legged Cat Productions. Mark Rance, Producer. Francois Marand, Editor and Mixer. Danica Kanonan, Research. Copyright Artisan Entertainment 2001. All Rights Reserved.

Discover more from TWIN PEAKS BLOG

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.