Two days before Mark Frost and David Lynch’s Twin Peaks debuted on the ABC Television Network, the relatively new “Entertainment Weekly” magazine devoted several pages to the groundbreaking show in their April 6, 1990 issue. Here is an in-depth and archival look at the magazine thanks to an user of the Internet Archive.

WHAT IS ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY?

Created by Jeff Jarvis and founded by Michael Klingensmith, “Entertainment Weekly” was created as a sister magazine to People. It was positioned as a “consumer guide to popular culture, including movies, music, and book reviews, sometimes with video game and stage reviews, too.” The first issue was published on Feb. 16, 1990, roughly two months before Twin Peaks’ television debut.

The magazine continued as a weekly publication until the Aug. 2019 issue when it transitioned to a monthly issue model. On Feb. 9, 2022, Entertainment Weekly ceased print publication and moved to digital-only format. The final print issue was that of April 2022.

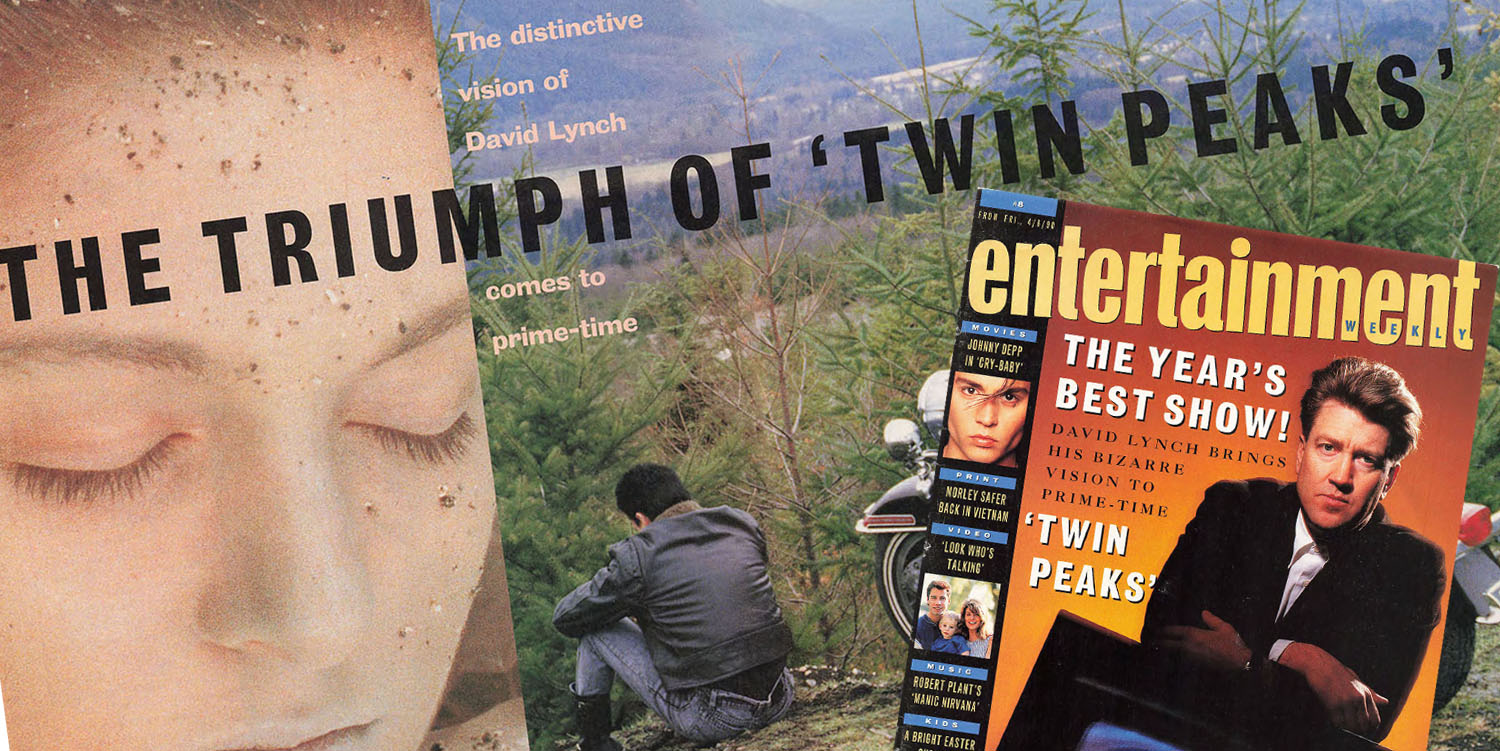

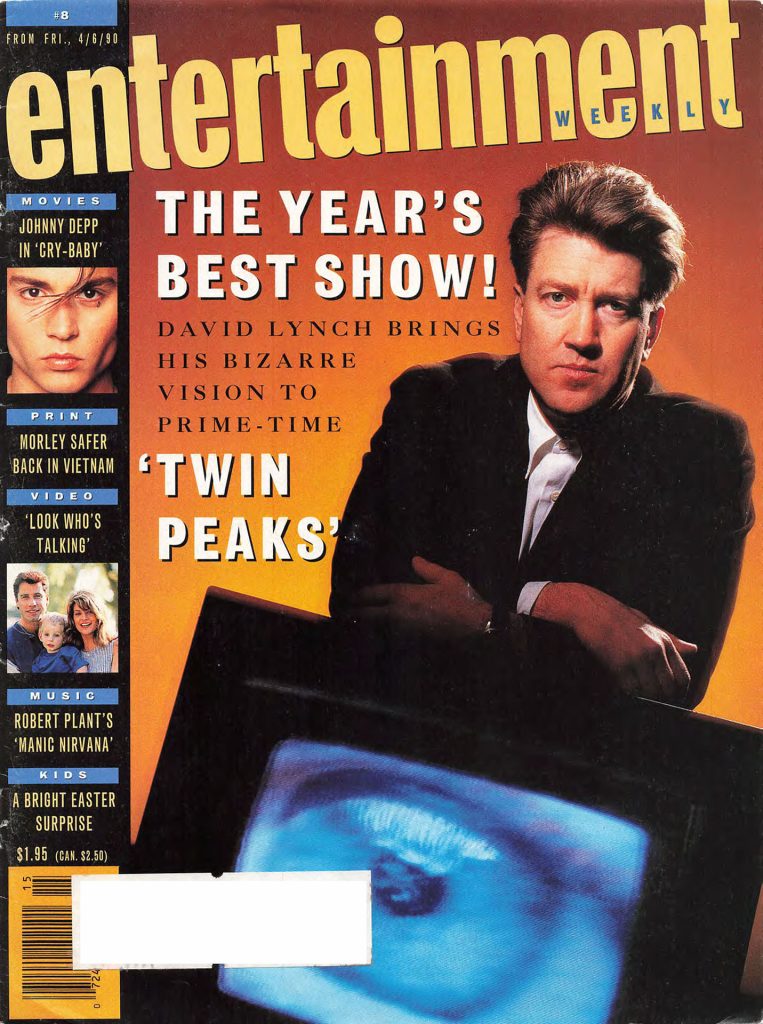

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY FROM APRIL 6, 1990 | COVER

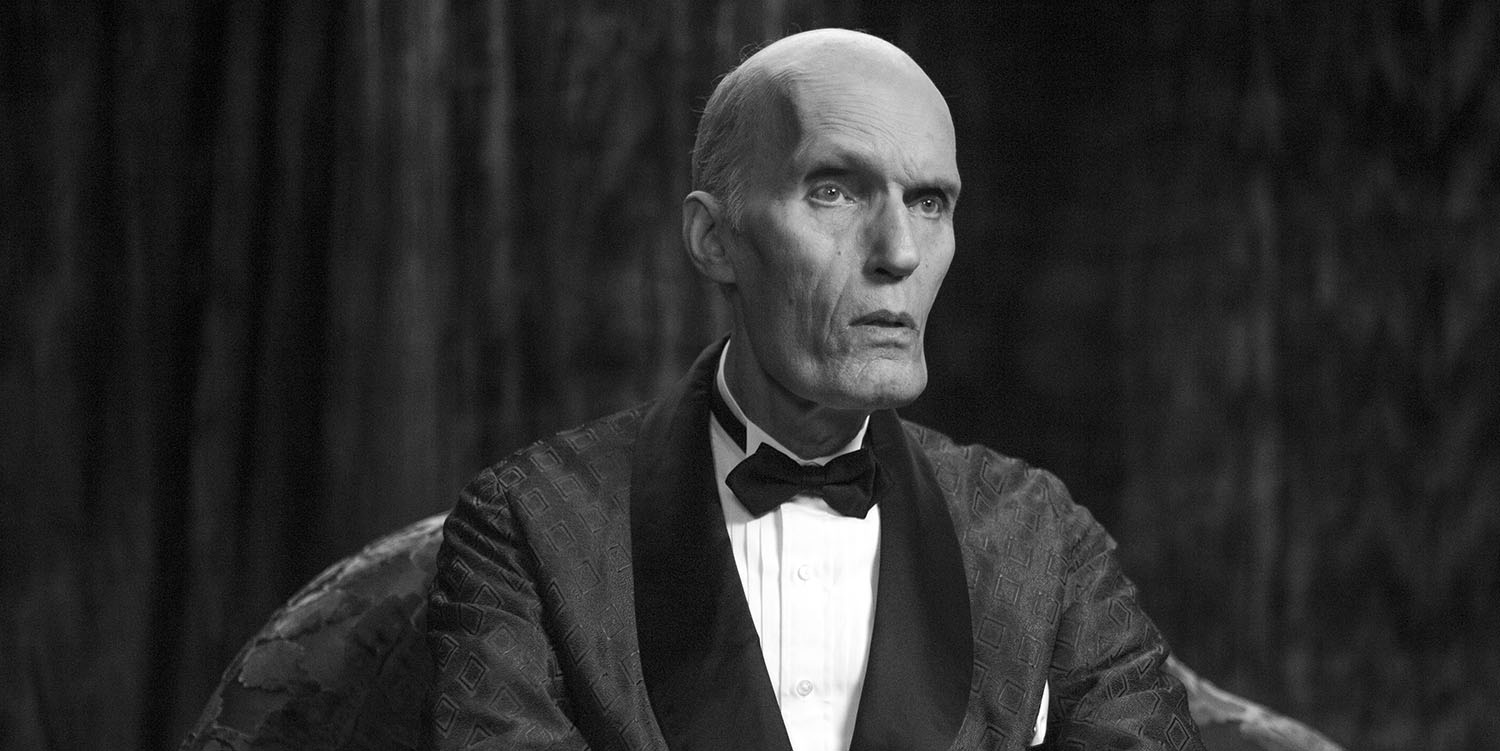

The cover of issue #8 from Friday, Apr. 6, 1990 featured David Lynch leaning against a television with a frozen image of Laura Palmer’s eye from the Twin Peaks pilot. The magazine proclaimed the upcoming series as “The Year’s Best Show.” Mark Hannauer [sic] took the photograph of Lynch, yet the magazine spelled his last name incorrectly. You can find Mark Hanauer’s work on his website and Instagram account today.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY FROM APRIL 6, 1990 | TABLE OF CONTENTS, PAGES 2-3

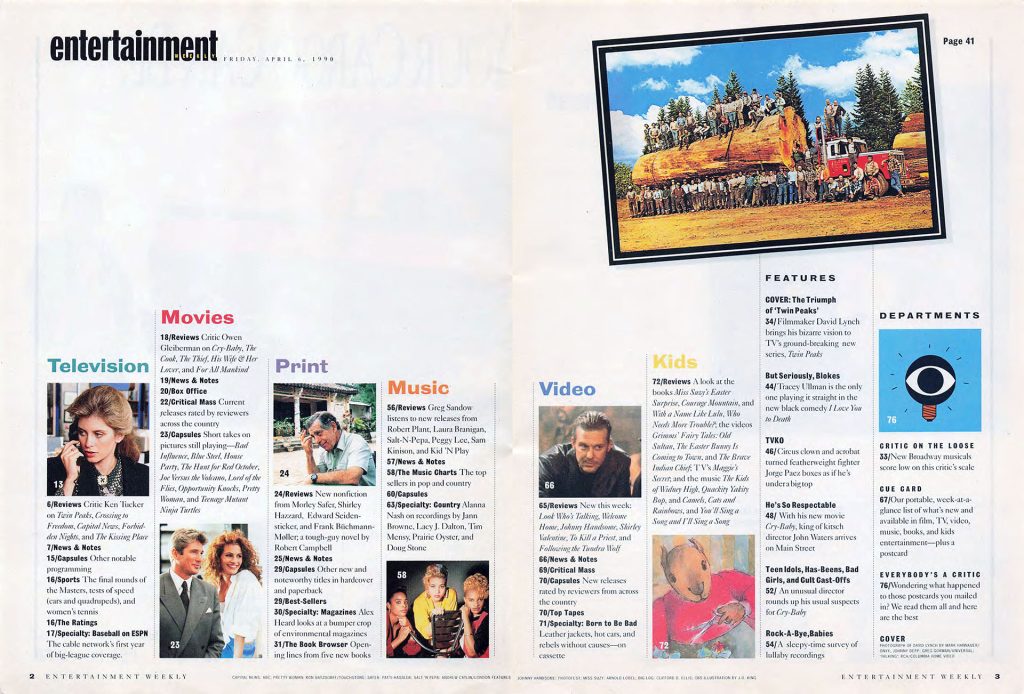

On pages 2-3, you will find the table of contents for issue #8. A synopsis of the cover story is found under the “Features” section: “COVER – The Triumph of ‘Twin Peaks’ / 34. David Lynch brings his bizarre vision to TV’s ground-breaking new series, Twin Peaks.”

A postcard from Western Washington is printed on page 3, which calls out a story on “page 41,” It would be the first of many stories from media about the real Twin Peaks of Snoqualmie Valley, Washington.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY FROM APRIL 6, 1990 | PAGES 6-8, 11

Pages 6-7 contains a review by Ken Tucker, the first of several stories about Twin Peaks found in this issue. Tucker would stay at the magazine until Feb. 2013. He posted a link to this original review following David Lynch’s passing in Jan. 2025.

TELEVISION

By: Ken Tucker

THE ARRIVAL OF DAVID LYNCH’S “Twin Peaks,” the most eagerly anticipated series of the season, threatens to make everything else on television this week seem irrelevant; why, not even Melissa Gilbert as a supporter of Chinese revolution in Tuesday’s Forbidden Nights can top the surpassing oddness of Lynch’s creation.

DIRECTOR DAVID Lynch says, “The thing is about secrets.” The “thing” is Twin Peaks, the wingdingiest thing to make it onto network television in many a full moon. In an already over quoted quote about his ominous, enthralling new prime-time soap opera, Lynch has called Twin Peaks “Peyton Place meets Blue Velvet” It’s that and more. It’s Mayberry R.F.D. Goes Psycho; Pee-wee’s Playhouse Has a Nervous Breakdown; and the first you-really-can’t-miss-this show of the ’90s.

At the start of Twin Peaks, the body of a young woman, wrapped in plastic. washes ashore in a small Northwestern mill village. The girl’s blue-veined, death-frosted skin is in startling contrast to the lush, warm greens and blues of this verdant land. There’s a stately beauty to the way Lynch shoots the discovery of the corpse of Laura Palmer, a popular local girl, but even as you’re becoming absorbed in the mystery of who killed her, Lynch and cowriter Mark Frost begin toying with their story’s tone and rhythm.

The local police chief is improbably named Harry S. Truman, and he’s played by Michael Ontkean, 16 years ago a rookie on The Rookies. Sheriff Truman is a pretty standard strong, silent type, but he has a gangling, neurotic deputy who collapses into racked sobbing upon seeing Laura’s body. “Come on,” Truman hisses dis-gustedly, “is this gonna happen every damn time?” Very quickly, subplots surface: a power play for the ownership of the town’s chief employer.

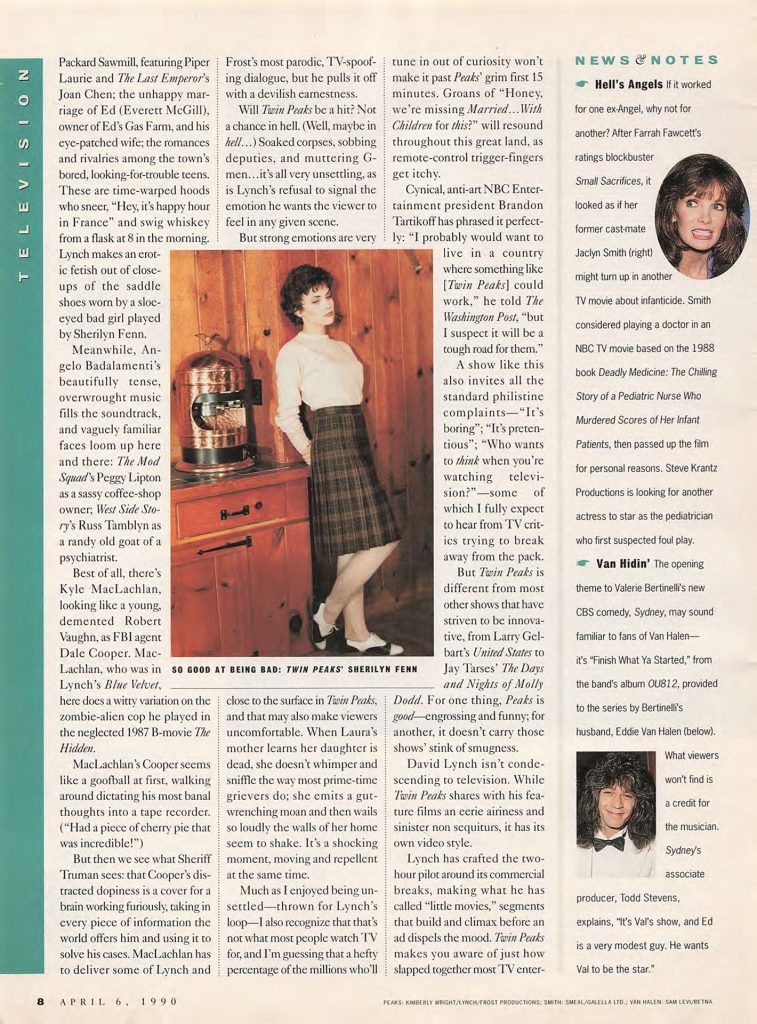

Packard Sawmill, featuring Piper Laurie and The Last Emperor’s Joan Chen; the unhappy marriage of Ed (Everett McGill), owner of Ed’s Gas Farm, and his eye-patched wife; the romances and rivalries among the town’s bored, looking-for-trouble teens. These are time-warped hoods who sneer, “Hey, it’s happy hour in France” and swig whiskey from a flask at 8 in the morning. Lynch makes an erotic fetish out of close-ups of the saddle shoes worn by a sloe-eyed bad girl played by Sherilyn Fenn.

Meanwhile, Angelo Badalamenti’s beautifully tense, overwrought music fills the soundtrack, and vaguely familiar faces loom up here and there: The Mod Squad’s Peggy Lipton as a sassy coffee-shop owner; West Side Story’s Russ Tamblyn as a randy old goat of a psychiatrist.

Best of all, there’s Kyle MacLachlan, looking like a young, demented Robert Vaughn, as FBI agent Dale Cooper. Mac-Lachlan, who was in Lynch’s Blue Velvet, here does a witty variation on the zombie-alien cop he played in the neglected 1987 B-movie The Hidden.

MacLachlan’s Cooper seems like a goofball at first, walking around dictating his most banal thoughts into a tape recorder. (“Had a piece of cherry pie that was incredible!”)

But then we see what Sheriff Truman sees: that Cooper’s distracted dopiness is a cover for a brain working furiously, taking in every piece of information the world offers him and using it to solve his cases. MacLachlan has to deliver some of Lynch and Frost’s most parodic, TV-spoof-ing dialogue, but he pulls it off with a devilish earnestness. Will Twin Peaks be a hit? Not a chance in hell. (Well, maybe in hell…) Soaked corpses, sobbing deputies, and muttering G-men…it’s all very unsettling, as is Lynch’s refusal to signal the emotion he wants the viewer to feel in any given scene. But strong emotions are very close to the surface in pain Peaks, and that may also make viewers uncomfortable. When Laura’s mother learns her daughter is dead, she doesn’t whimper and sniffle the way most prime-time grievers do; she emits a gut-wrenching moan and then wails so loudly the walls of her home seem to shake. les a shocking moment, moving and repellent at the same time.

Much as I enjoyed being tin-settled—thrown for Lynch’s loop—I also recognize that that’s not what most people watch TV for, and I’m guessing that a hefty percentage of the millions who’ll tune in out of curiosity won’t make it past Peaks’ grim first 15 minutes. Groans of “Honey, we’re missing Married … With Children for this?” will resound throughout this great land, as remote-control trigger-fingers get itchy.

Cynical, anti-art NBC Entertainment president Brandon Tartikoff has phrased it perfectly: “I probably would want to live in a country where something like [Twin Peaks] could work,” he told The Washington Post, “but I suspect it will be a tough road for them.”

A show like this also invites all the standard philistine complaints—”It’s boring”; “It’s pretentious”; “Who wants to think when you’re watching television?”—some of which I fully expect to hear from TV critics trying to break away from the pack.

But Twin Peaks is different from most other shows that have striven to be innovative, from Larry Gelbart’s United States to Jay Tarses’ The Days and Nights of Molly Dodd. For one thing, Peaks is good—engrossing and funny; for another, it doesn’t carry those shows’ stink of smugness.

David Lynch isn’t condescending to television. While Twin Peaks shares with his feature films an eerie airiness and sinister non sequiturs, it has its own video style. Lynch has crafted the two-hour pilot around its commercial breaks, making what he has called “little movies,” segments that build and climax before an ad dispels the mood.

Twin Peaks makes you aware of just how slapped together most TV entertainment is; its calm, deliberate eccentricity is a virtue in itself.

ABC continues to be the only network taking bold changes. Elvis may or may not be dead, but for seven more hour-long episodes starting April 12, the bodies and the non sequiturs will pile up, eccentricities will deepen into dementia and Twin Peaks will live. Be there. A+

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY FROM APRIL 6, 1990 | PAGES 34-38, 40, 42

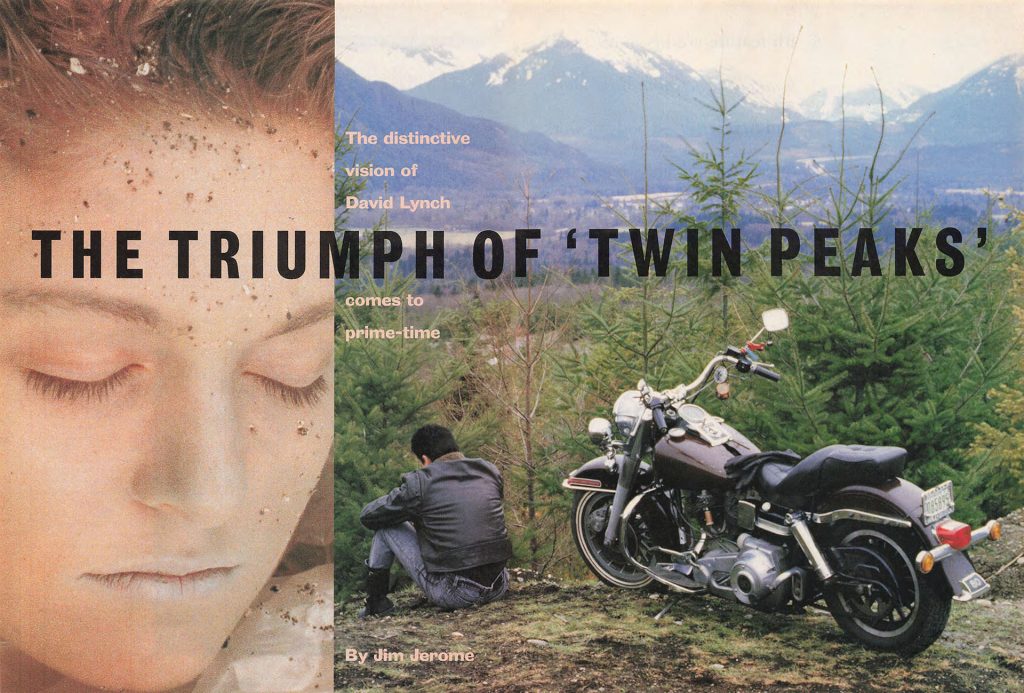

Jim Jerome’s cover story, titled “The Triumph of ‘Twin Peaks'” begins on pages 34-35 with images of Laura Palmer wrapped in plastic and James Hurley sitting on the mountain overlook with his Harley Davidson motorcycle. Kimberly Wright is credited with taking both images. She served as the on-set photographer during the location production in Snoqualmie Valley and Washington state during February to March 1989.

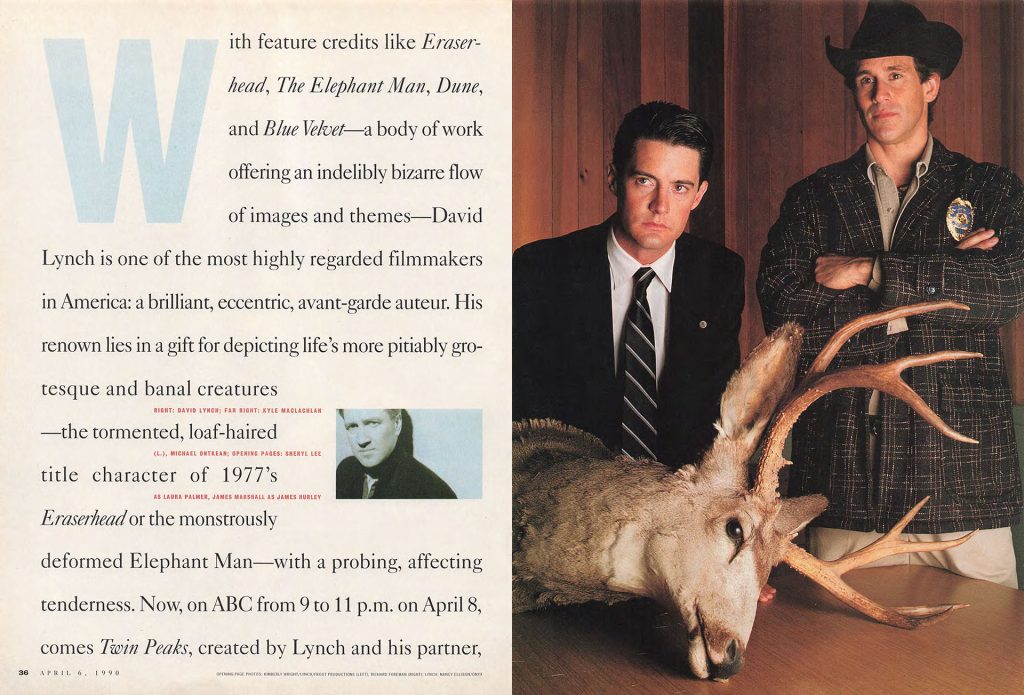

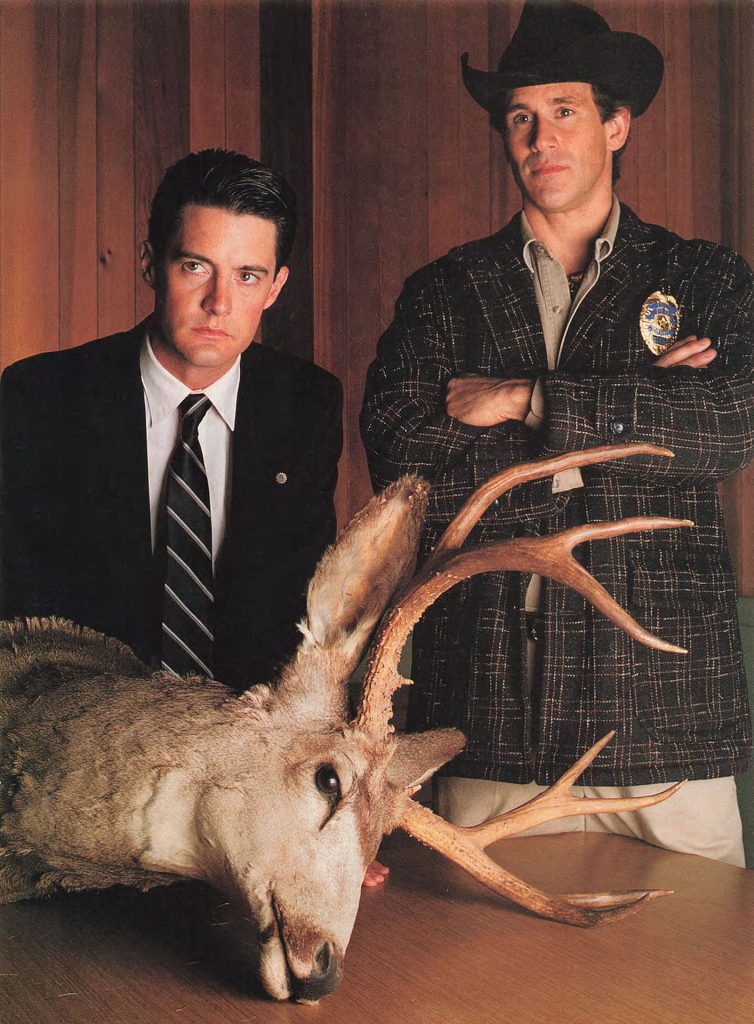

Page 36 contains an image of David Lynch taken by Nancy Ellison, which is opposite a publicity photo of Special Agent Dale Cooper and Sheriff Harry S. Truman next to a deer head on a table.

This photograph is credited to Richard Foreman who is, according to his website, “credited on over 150 feature films and countless television shows, working with many of Hollywood’s finest directors, producers, and actors.”

Jerome’s article begins on page 36:

With feature credits like Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, Dune and Blue Velvet – a body of work offering an indelibly bizarre flow of images and themes – David Lynch is one of the most highly regarded filmmakers in America: a brilliant, eccentric, avant-garde auteur. His renown lies in a gift for depicting life’s more pitiably grotesque and banal creatures – the tormented, loaf-haired title character of 1977’s Eraserhead or the monstrously deformed Elephant Man – with a probing, affecting tenderness. Now, on ABC from 9 to 11 p.m. on April 8, comes Twin Peaks, created by Lynch and his partner, Mark Frost

Twin Peaks is a fictional mountain town in the Pacific Northwest, shrouded by fog, Douglas firs, and all manner of Lynchian intrigues—sexUal, criminal, and financial—lurking beneath its cozy, idyllic surface.

The pilot plot kicks in when a high school girl, Laura Palmer, is found murdered, wrapped in plastic, on a shore. An FBI agent (played by Kyle MacLachlan, a Lynch “ensemble” regular from Dune and Blue Velvet) arrives in town and teams with the sheriff (Michael Ontkean) to find the killer. It’s soon evident that nothing in this weird place—or in the surreal cinema of David Lynch—is as it seems.

One thing that sets the pilot apart from most network fare is that after two hours the murder remains unsolved; that’s only one of many questions left unanswered. There aren’t the tidy wrap-ups and res-cues of television’s hour-long dramas; loose ends are all over the place. Everyone in town seems to have at least one illicit fling going, and there arc hints that Laura, known as a model of innocence, was some-how linked to cocaine and an X-rated singles network. The only truly crazy guy in town is the wild-eyed shrink who had seen the dead girl in therapy. [See Ken Tucker’s review, page 6.]

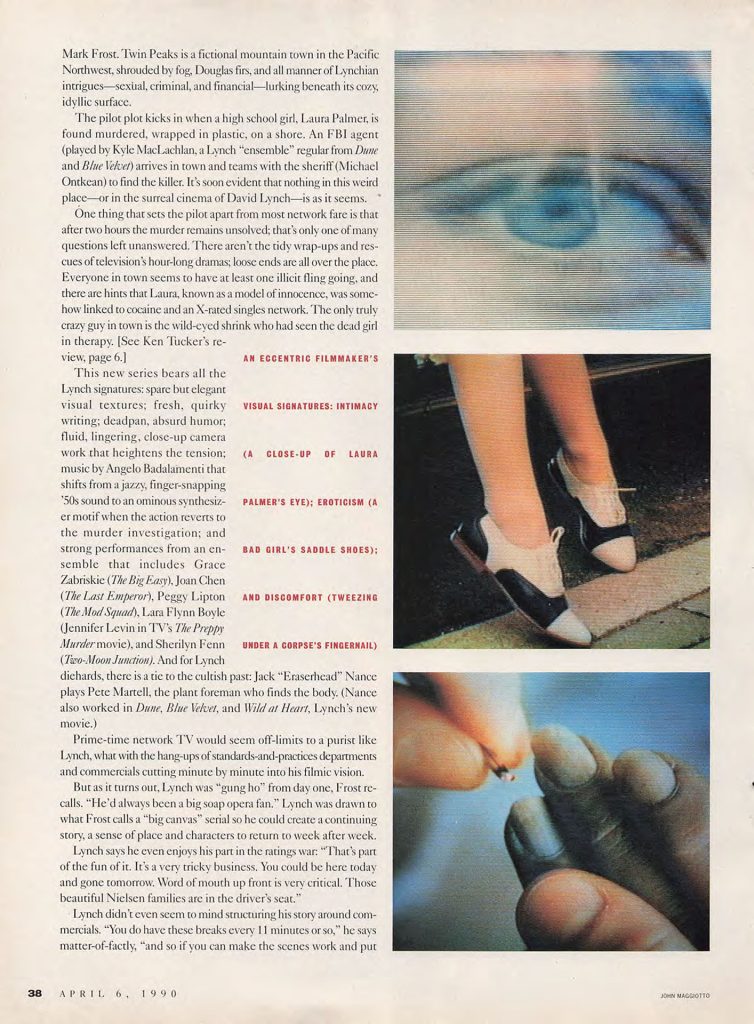

This new series bears all the Lynch signatures: spare but elegant visual textures; fresh, quirky writing; deadpan, absurd humor; fluid, lingering, close-up camera work that heightens the tension; music by Angelo BadalaMenti that shifts from a jazzy, finger-snapping ’50s sound to an ominous synthesizer motif when the action reverts to the murder investigation; and strong performances from an ensemble that includes Grace Zabriskie (The Big Easy), Joan Chen (The Last Emperor), Peggy Lipton (The Mod Squad), Lara Flynn Boyle (Jennifer Levin in TV’s The Preppy Murder movie), and Sherilyn Fenn (Two-Moon Junction). And for Lynch diehards, there is a tic to the cultish past: Jack “Eraserhead” Nance plays Pete Martell, the plant foreman who finds the body. (Nance also worked in Dune, Blue Velvet, and Wild at Heart, Lynch’s new movie.)

Prime-time network TV would seem off-limits to a purist like Lynch, what with the hang-ups of standards-and-practices departments and commercials cutting minute by minute into his filmic vision.

But as it turns out, Lynch was “gung ho” from day one, Frost recalls. “He’d always been a big soap opera fan.” Lynch was drawn to what Frost calls a “big canvas” serial so he could create a continuing story, a sense of place and characters to return to week after week.

Lynch says he even enjoys his part in the ratings war: “That’s part of the fun of it. It’s a very tricky business. You could be here today and gone tomorrow Word of mouth up front is very critical. Those beautiful Nielsen families are in the driver’s seat.”

Lynch didn’t even seem to mind structuring his story around commercials. “You do have these breaks every 11 minutes or so,” he says matter-of-factly, “and so if you can make the scenes work and put

[the story continues on page 40]

a couple together, you hit a commercial and then it’s a whole new ball game when you come back. You do find yourself thinking in terms of making these little 11-minute movies, and it’s kinda neat.” (Actually, there will be five commercial breaks in the Twin Peaks premiere instead of the standard seven.)

ABC Entertainment president Robert A. Iger, who inherited the project, calls the Lynch experiment “a case of a network having the desire and guts to try different television forms, in part to continue to maintain a dominance over the overall TV world. We are always looking to break new barriers and find the breakout program. [ABC also recently signed creative powerhouse James L. Brooks (the movies Terms of Endearment and Broadcast News, the Fox network’s Tracey Ullman Show) to develop three comedy series.]

“Sure, there is some risk involved whenever you do something as different as this,” Iger says. “And the feel of this program is unlike that of any other program on TV But even to say ‘risk’ implies a lack of confidence I have in the show, which wouldn’t be correct.”

The task of translating Lynch’s mystique into a prime-time pitch was eased somewhat with Frost—who had been a writer and story editor on Hill Street Blues — on board as the proven Mr. Inside.

Cap Cities/ABC didn’t flinch when Lynch and Frost brought in their idea. “They would have been concerned with my image,” Lynch admits, “had I come in on my own. Mark took the edge off and made me more presentable. Helped me stay on the highway.”

Brandon Stoddard, Igers’ predecessor, ordered the two-hour pilot for a possible fall ’89 series. He then left the entertainment-division presidency in March 1989, as Lynch went into production.

Iger and his creative team took over from Stoddard and saw dailies and met with Frost and Lynch to get the “arc” of the stories and characters. By late May. Iger had seen the rough cut of the pilot and ordered the remaining seven hours.

Lynch directed the pilot a year ago on locations near Seattle at a cost approaching $4 million. (The hour-long episodes took a week each and averaged $1 million.) The absorbing, atmospheric pilot was written by Lynch and Frost, who first teamed up to write a script that was never produced based on Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe.

“David doesn’t type too well,” Frost says, “so I sit at the keyboard and we literally write every word together. We’ll talk for a while and then find some way to avoid working and get a cup of coffee, the usual routine.”

The process was the same for the second episode, which Lynch also directed. Lynch then went off to finish Wild at Heart, while Frost wrote the remaining segments, with revising and shaping help from two writers. Frost directed the final hour, and five other directors—including Tim Hunter (River’s Edge) and Caleb Deschanel (Crusoe)—did one each, with Lynch popping in as story consultant.

[the story concluded on page 42]

Peaks epitomizes the fundamental conflict facing prime-time programmers. As a high-ranking non-ABC-network exec says, “Most people here do not expect that Peaks will work. The critics and audiences give us signals like ‘We’re tired of what we’ve seen before; don’t give us more of the same.’ But when you venture out there, there arc not a lot of indications that they’re embracing what’s different….

“It’s like a wife-mistress thing. ‘Yeah, we wanna get it down and dirty, I want that choice in my life, but I wanna come home to a good mother.’…In some ways, maybe what David will be is the martyr who will push the boundaries—expand what [network] TV can do and should do—without being wholly successful.”

One member of the Lynch ensemble, often said to be the director’s screen alter ego, doesn’t necessarily subscribe to the martyr theory. “Knowing David a little bit,” actor Kyle MacLachlan says, “I think it’s exciting to combine him with television….Any new media where he can create pushes him forward. I absolutely think this will he controversial; it will be watched.”

For all of Lynch’s enthusiasms about television and Twin Peaks, he says he “had some misgivings in the beginning. It’s real important for me to do something a certain way without someone else coming through after you’re done and changing everything. There haven’t been any of the horror stories you hear on this show—yet.”

Lynch’s worries about TV work were understandably rooted in the twin piques faced by most writer-directors in a medium subsidized largely by advertising revenues: censorship and corporate meddling. But he sailed through. The standards-and-practices people, Frost reports, found just one objectionable scene in all nine hours of film: an extreme close-up in the pilot on MacLachlan’s hand as he slides a tweezer under the corpse’s fingernail and removes a tiny “R,” a clue to her murder.

Says Frost: “They wanted [the scene’ to be shorter. They said it made them uncomfortable.” But the creative team dug in its own nails, and the scene remained.

Lynch praises the network for letting him go about his work with uncompromised autonomy. “I might as well have had final cut,” he says. “I got to do the film I wanted and direct it the way I wanted. “l’hey treated the show with a lot of respect.”

The picture on the small screen is looking bigger and sharper every day to Lynch. I le and Frost have signed with the Fox network to cocreate and codirect what Frost describes as a series of reality-based “docupoems,” such as the Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Their first segment will air later in the spring. This time, Frost says, “it’s MTV meets 60 in 30 minutes.”

Next: 30 seconds. Lynch recently made his debut as an ad director on a new spot for Yves Saint Laurent’s Opium fragrance. “It’s got an Oriental theme, a woman opening the bottle. It’s a very sensual commercial,” Lynch says with typical exuberance. “You’d know it if you saw it. I really had a blast doing it. I’ve also done a public service announcement for New York City on trash and rats. It’s in black and white. And I had a really good time doing that.”

Lynch, in fact, seems capable of having a pretty good time on al-most any creative project as long as it doesn’t smack of being too safe. Even if Twin Peaks is not a commercial success, the director deserves considerable credit for taking a chance. “Look,” he says, “everything we do in this business is a risk. The more success you have, the more you second-guess all your future projects. You have to be ready to fail and try these things. It’s kind of a diabolical thing but you can’t really think about it. And I didn’t. I lucked out.”

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY FROM APRIL 6, 1990 | PAGE 39

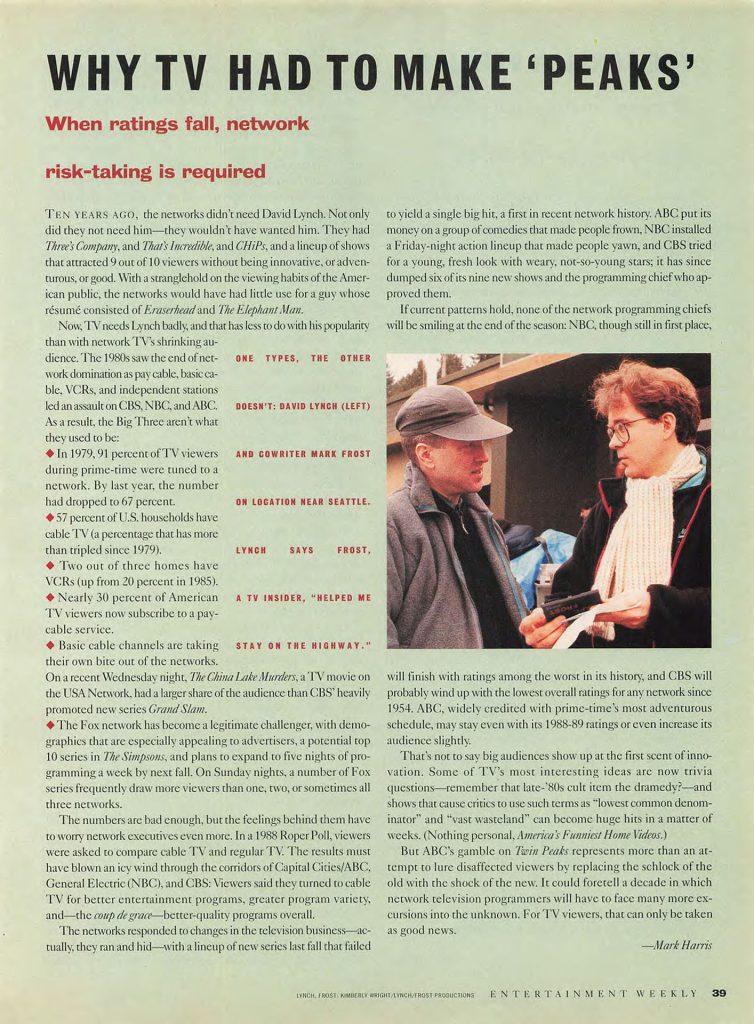

On page 39, Mark Harris wrote a story about “Why TV Had to Make Twin Peaks: when ratings fall, network risk-taking is required.” Harris contends that Lynch was needed for network television as television networks were facing shrinking audiences. With popularity of cable, independent stations and VCRs throughout the 1980s, the big three networks – NBC, ABC and CBS – weren’t what they used to be.

“But ABC’s gamble on Twin Peaks represents more than an attempt to lure disaffected viewers by replacing the schlock of the old with the shock of the new,” writes Harris. “It could foretell a decade in which network television programmers will have to face many more excursions into the unknown. For TV viewers, that can only be taken as good news.”

The image of Lynch and Frost was taken by Kimberly Wright outside the Weyerhaeuser Sawmill Office in Snoqualmie, Washington. It was first seen in the Sept. 1989 issue of Connoisseur magazine which gave the world a first look at Twin Peaks.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY FROM APRIL 6, 1990 | PAGES 40-41

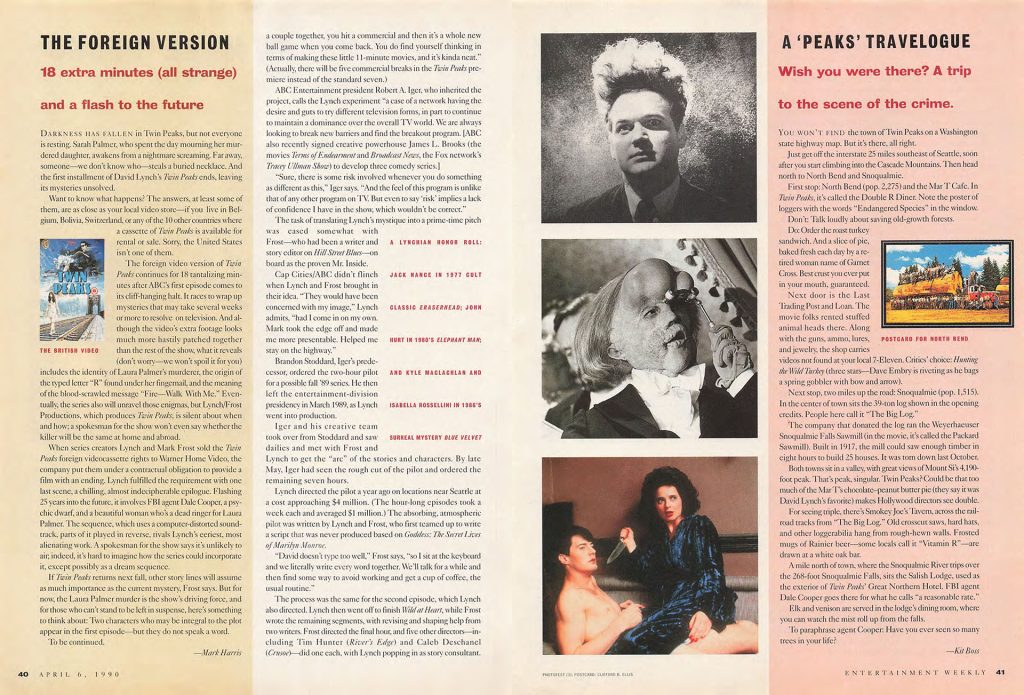

Pages 40-41 contain three stories with one being a continuation of Jim Jerome’s cover story. In “The Foreign Version,” Mark Harris details the famous International version for the Twin Peaks pilot which debuted on VHS in the European market on Friday, Dec. 8, 1989.

Harris writes about the video cassette: “The answers, at least some of them, are as close as your local video score—if you live in Belgium, Bolivia, Switzerland, or any of the 10 other countries where a cassette of Twin Peaks is available for rental or sale. Sorry, the United States isn’t one of them.

The foreign video version of Twin Peaks continues for 18 tantalizing minutes after ABC’s first episode comes to its cliff-hanging halt. It races to wrap up mysteries that may take several weeks or more to resolve on television. And although the video’s extra footage looks much more hastily patched together than the rest of the show; what it reveals (don’t worry—we won’t spoil it for you) includes the identity of Laura Palmer’s murderer, the origin of the typed letter “R” found under her fingernail, and the meaning of the blood-scrawled message – Fire Walk With Me.”

Eventually, the series also will unravel those enigmas, but Lynch/Frost Productions, which produces Twin Peaks, is silent about when and how; a spokesman for the show won’t even say whether the killer will be the same at home and abroad. When series creators Lynch and Mark Frost sold the Twin Peaks foreign videocassette rights to Warner Home Video, the company put them under a contractual obligation to provide a film with an ending. Lynch fulfilled the requirement with one last scene, a chilling, almost indecipherable epilogue.

Flashing 25 years into the future, it involves FBI agent Dale Cooper, a psychic dwarf, and a beautiful woman who’s a dead ringer for Laura Palmer. The sequence, which uses a computer-distorted soundtrack, parts of it played in reverse, rivals Lynch’s eeriest, most alienating work. A spokesman for the show says it’s unlikely to air; indeed, it’s hard to imagine how the series could incorporate it, except possibly as a dream sequence. If Twin Peaks returns next fall, other story lines will assume as much importance as the current mystery, Frost says.

But for now, the Laura Palmer murder is the show’s driving force, and for those who can’t stand to be left in suspense, here’s something to think about: Two characters who may be integral to the plot appear in the first episode—but they do not speak a word. To be continued.”

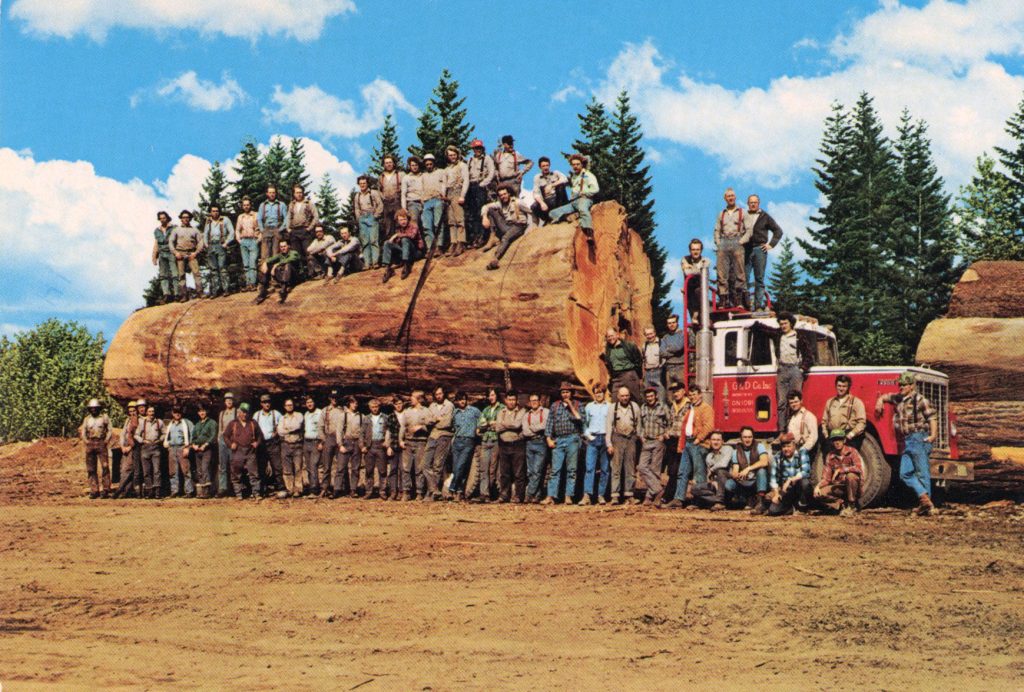

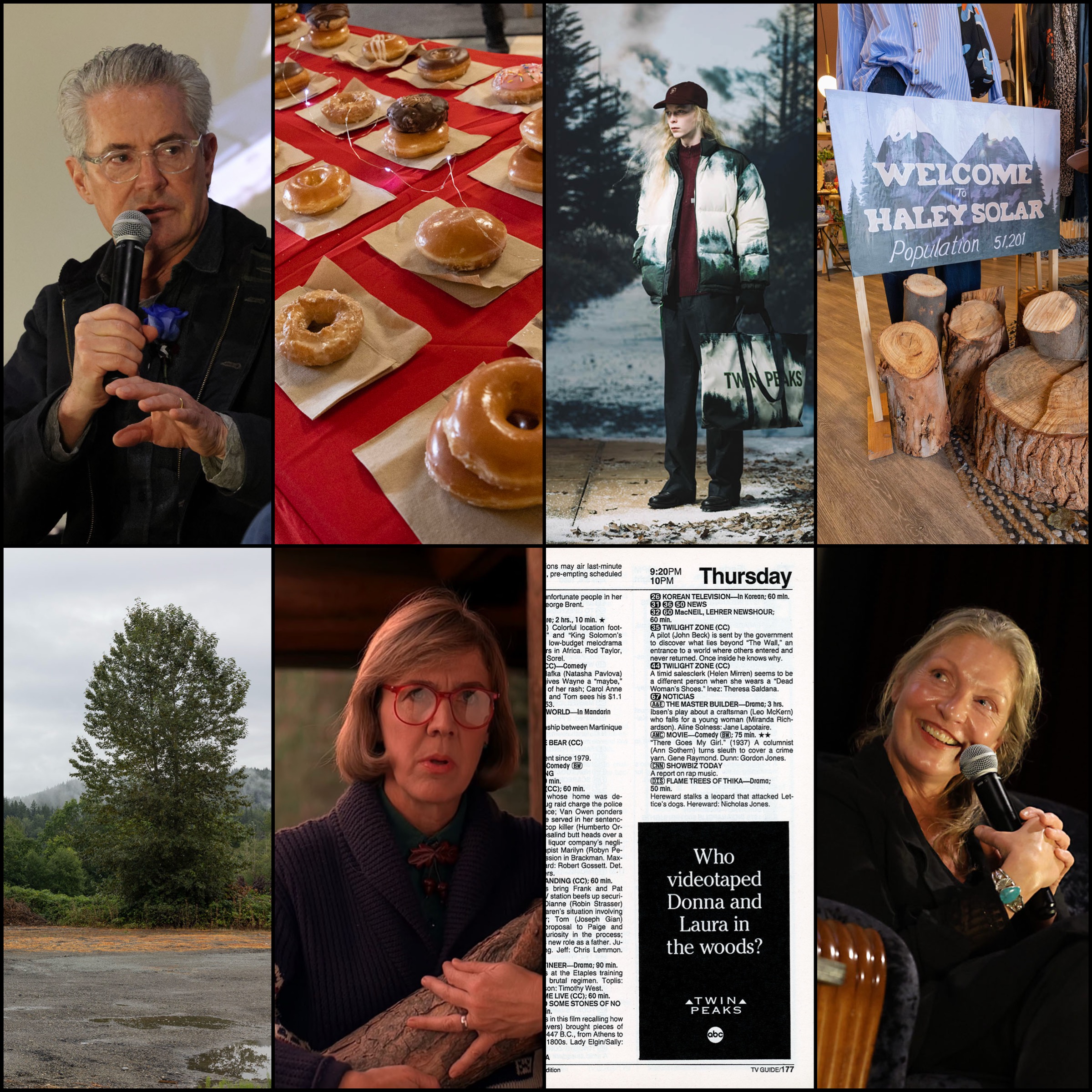

The third story on this two-page spread is about Kit Boss’ visit to Snoqualmie Valley, Washington. It includes a postcard image of a logging crew and giant log on a truck bed. The back of the original postcard gave the following description: Giant fir log from the forests of Western Washington. This log is 11 1/2 feet across the butt and contained 13,700 board feet. The logging crew shown here was proud of this one.

A ‘PEAKS’ TRAVELOGUE

Wish you were there? A trip to the scene of the crime.

YOU WON’T FIND the town of Twin Peaks on a Washington state highway map. But it’s there, all right.

Just get off the interstate 25 miles southeast of Seattle, soon after you start climbing into the Cascade Mountains. Then head north to North Bend and Snoqualmie.

First stop: North Bend (pop. 2,275) and the Mar T Cafe. In Twin Peaks, it’s called the Double R Diner. Note the poster of loggers with the words “Endangered Species” in the window.

Don’t: Talk loudly about saving old-growth forests.

Do: Order the roast turkey sandwich. And a slice of pie, baked fresh each day by a retired woman name of Garnet Cross. Best crust you ever put in your mouth, guaranteed.

Next door is the Last Trading Post and Loan. The movie folks rented stuffed animal heads there. Along with the guns, ammo, lures, and jewelry, the shop carries videos not found at your local 7-Eleven. Critics’ choice: Hunting the Wild Turkey (three stars—Dave Embry is riveting as he bags a spring gobbler with bow and arrow).

Next stop, two miles up the road: Snoqualmie (pop. 1,515). In the center of town sits the 39-ton log shown in the opening credits. People here call it “The Big Log.”

The company that donated the log ran the Weyerhaeuser Snoqualmie Falls Sawmill (in the movie, it’s called the Packard Sawmill). Built in 1917, the mill could saw enough timber in eight hours to build 25 houses. It was torn down last October.

Both towns sit in a valley, with great views of Mount Si’s 4,190-foot peak. That’s peak, singular. Twin Peaks? Could be that too much of the Mar T’s chocolate–peanut butter pie (they say it was David Lynch’s favorite) makes Hollywood directors see double.

For seeing triple, there’s Smokey Joe’s Tavern, across the rail-road tracks from “The Big Log.” Old crosscut saws, hard hats, and other loggerabilia hang from rough-hewn walls. Frosted mugs of Rainier beer—sonic locals call it “Vitamin R”—are drawn at a white oak bar.

A mile north of town, where the Snoqualmie River trips over the 268-foot Snoqualmie Falls, sits the Salish Lodge, used as the exterior of Twin Peaks’ Great Northern Hotel. FBI agent Dale Cooper goes there for what he calls “a reasonable rate.”

Elk and venison are served in the lodge’s dining room, where you can watch the mist roll up from the falls.

To paraphrase agent Cooper: Have you ever seen so many trees in your life?

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY FROM APRIL 6, 1990 | PAGES 42-43

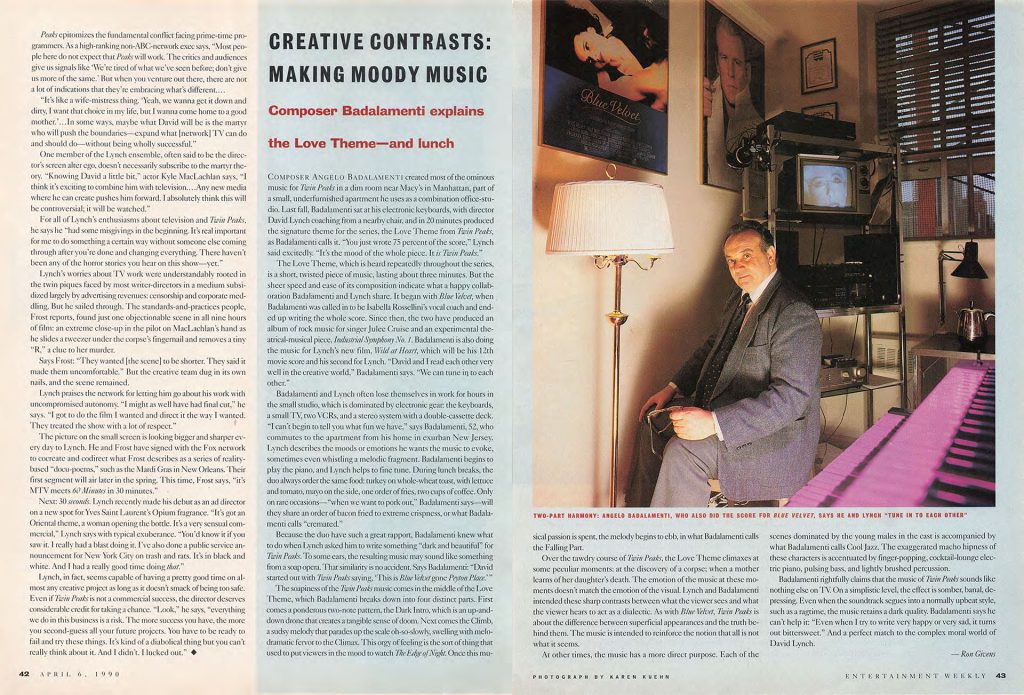

Ron Givens provides the final story about Twin Peaks on pages 42-43 by interviewing the maestro, Angelo Badalamenti. His photograph was taken by New Mexico-based photographer Karen Kuehn.

CREATIVE CONTRASTS: MAKING MOODY MUSIC Composer Badalamenti explains

the Love Theme—and lunch

COMPOSER ANGELO BADALAMENTI created MOST of the ominous’ music for Twin Peaks in a dim room near Macey’s in Manhattan, part of a small, underfurnished apartment he uses as a combination office-studio. Last fall, Badalamenti sat at his electronic keyboards, with director David Lynch coaching from a nearby chair, and in 20 minutes produced the signature theme for the series, the Love Theme from Twin Peaks, as Badalamenti calls it. “You just wrote 75 percent of the score,” Lynch said excitedly. “It’s the mood of the whole piece. It is Twin Peaks.”

The Love Theme, which is heard repeatedly throughout the series, is a short, twisted piece of music, lasting about three minutes. But the sheer speed and ease of its composition indicate what a happy collab-oration Badalamenti and Lynch share. It began with Blue Velvet, when Badalamenti was called in to be Isabella Rossellini’s vocal coach and ended up writing the whole score. Since then, the two have produced an album of rock music for singer Juice Cruise and an experimental theatrical musical piece, Industrial Symphony NO. 1. Badalamenti is also doing the music for Lynch’s new film, Wild at Heart, which will be his 12th movie score and his second for Lynch. “David and I read each other very well in the creative world,” Badalamenti says. “We can tune in to each other.”

Badalamenti and Lynch often lose themselves in work for hours in the small studio, which is dominated by electronic gear: the keyboards, a small TV two VCRs, and a stereo system with a double-cassette deck. “I can’t begin to tell you what fun we have,” says Badalamenti, 52, who commutes to the. apartment from his home in .exurban New Jersey. Lynch describes the moods or emotions he wants the music to evoke, sometimes even whistling a melodic fragment. Badalamenti begins to play the piano, and Lynch helps to fine tune. During lunch breaks, the duo always order the same food: turkey on whole-wheat toast, with lettuce and tomato, mayo on the side, one order of fries, two cups of coffee. Only on rare occasions–“when we want to pork out,” Badalamenti says—will they share an order of bacon fried to extreme crispness, or what Badalamenti calls “cremated.”

Because the duo have, such a great rapport, Badalamenti knew what to do when Lynch asked him to write something “dark and beautiful” for Twin Peaks. To some cars, the resulting music may sound like something from a soap opera. That similarity is no accident. Says Badalamenti: “David started out with &fin Path saying, ‘This is Blue Velvet gone Peyton Place.”

The soapiness of the Twin Peaks music comes in the middle of the Love Theme, which Badalamenti breaks down into four distinct parts. First conies a ponderous two-note pattern, the Dark limo, which is an up-and-down drone that creates a tangible sense of doom. Next comes the Climb, a sudsy melody that parades up the scale oh-so-slowly, swelling with melodramatic fervor to the Climax.. This orgy of feeling is the sort of thing that used to put viewers in the mood to watch The Edge of Night. Once this musical passion is spent, the melody begins to ebb, in what Badalamenti calls the Falling Part.

Over the tawdry course of Twin Peaks, the Love l’heme climaxes at some peculiar moments: at the discovery of a corpse; when a mother learns of her daughter’s death. The emotion of the music at these moments doesn’t match the emotion of the visual. Lynch and Badalamenti intended these sharp contrasts between what the viewer sees and what the viewer hears to act as a dialectic. As with Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks is about the difference between superficial appearances and the truth behind them. The music is intended to reinforce the notion that all is not what it seems.

At other times, the music has a more direct purpose. Each of the scenes dominated by the young males in the cast is accompanied by what Badalamenti calls Cool Jazz. The exaggerated macho hipness of these characters is accentuated by finger-popping, cocktail-lounge electric piano, pulsing bass, and lightly brushed percussion.

Badalamenti rightfully claims that the music of Twin Peaks sounds like nothing else on TV. On a simplistic level, the effect is somber, banal, de-pressing. Even when the soundtrack segues into a normally upbeat style, such as a ragtime, the music retains a dark quality. Badalamenti says he can’t help it: “Even when I try to write very happy or very sad, it turns out bittersweet.” And a perfect match to the complex moral world of David Lynch.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY FROM APRIL 6, 1990 | PAGE 68

The final mention of Twin Peaks in issue #8 is found in The Cue Card section on page 68. Under Sunday 4/8, a brief mention is made of the show:

Twin Peaks ABC (9-11 p.m.) The debut of David Lynch’s uneasy, queasy prime time soap. Don’t miss it. A+

Another mention is made of episode 1.001 on Thursday, 4/12:

Twin Peaks ABC (9-10 p.m.) New series in regular time slot.

Only a few days after this issue was published, the world would be forever changed when Twin Peaks aired on ABC.

Discover more from TWIN PEAKS BLOG

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.