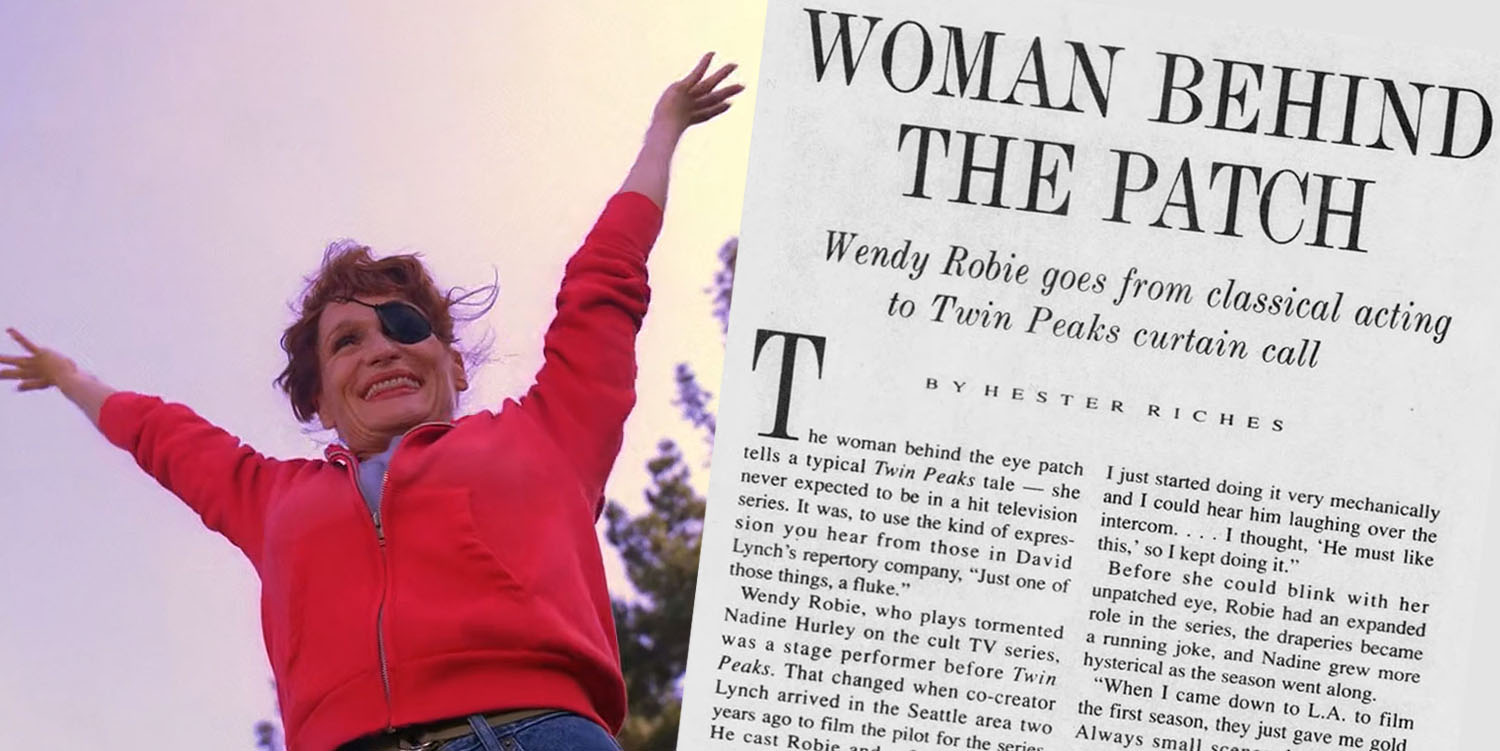

Audio commentaries from Directors, writers and crew members who worked on David Lynch and Mark Frost’s Twin Peaks were found on the first season DVD set from Artisan Home Entertainment. Released in December 2001, this set was the first time the series was offered on DVD. The inclusion of these commentaries offered a rare behind-the-scenes at how each episode was created. For episode 1.003, Director Tina Rathborne shared her insights and experience working on this wonderful and strange show.

TWIN PEAKS EPISODE 1.003 AUDIO COMMENTARY BY TINA RATHBORNE

The audio commentary from Tina Rathborne is found under the “Episode Features” tab after selecting “Ep. 3” from the Disc Two DVD Menu.

[Voiceover from Michael J. Anderson plays over the “Previously on Twin Peaks” montage] Tina Rathborne directed episode three. She met David Lynch when she cast him in her feature Zelly and Me. We interviewed Tina for this commentary on the lawn of her home in Maine.

[Tina Rathborne] Because I had never watched a great deal of TV, I really, it didn’t seem risqué to me. But off that subject and more on the subject of what we were doing, it did feel like we were making a feature film, but on a very tight budget and a tight budget where you were handed most of your sets, costumes. I mean, there were a lot of givens, but I felt that I did have the freedom to explore the corners of the characters that I was not being handed just stock characters.

And that there were pockets in the actors themselves that hadn’t been explored. You know, vulnerabilities, there is within the character that could be bloomed and that there was so much mystery surrounding the story itself that on some level, anything goes. And even in terms of the editing, I feel that David and Mark Frost didn’t ask us to change more than four things.

So that the intimacy of the first year where we were not in a fishbowl, nobody seemed to be watching us. We didn’t feel the presence of ABC hardly at all. And if you had a problem, you called the source. It felt like you were making a feature film or quasi-feature film. There was an enormous amount of freedom.

So except for time, which I found grueling, some of it felt “slam bam, thank you, ma’am.” But it was much more interesting than that.

I could choose my initial shot. I couldn’t change the scene. Yeah, we could change the scene order. In fact, I think we did change some scene orders. But I chose [Audrey Horne’s] face because I really thought, I think because I just found her face and lips very seductive to me. I mean, it was something I found very absorbing, and I wanted to start with that, something that absorbing.

She was very mysterious and powerful, in a kind of Marilyn Monroe sort of way. And since we all believed, I don’t know why, that Coop was going to have an affair with her, showing her in all her glory and then seeing him come down for breakfast, seemed to be emotionally right.

As far as I remember, we all believed that they were a couple or going to be a couple. And it seemed part, I mean, since the story is the seduction of–by innocence, you know, the town itself what role Laura Palmer and her beautiful young contemporaries represented was the innocence of America. And the seduction by them of the outsiders.

So Audrey’s seduction of Coop seems part of the dual lesson that Coop is learning. He’s learning about his more innocent side, and he’s learning about his darker side, that he’s willing to be seduced by this young girl. This young, somewhat raunchy girl. But he’s also willing to defend his higher side.

Since my episode, had a lot of sitting down and talking, whether it was at the hotel or whether it was at the diner, or whether it was at the police station. In fact, one of the things that was so much fun for me was having to figure out how to keep those sit down talk scenes interesting.

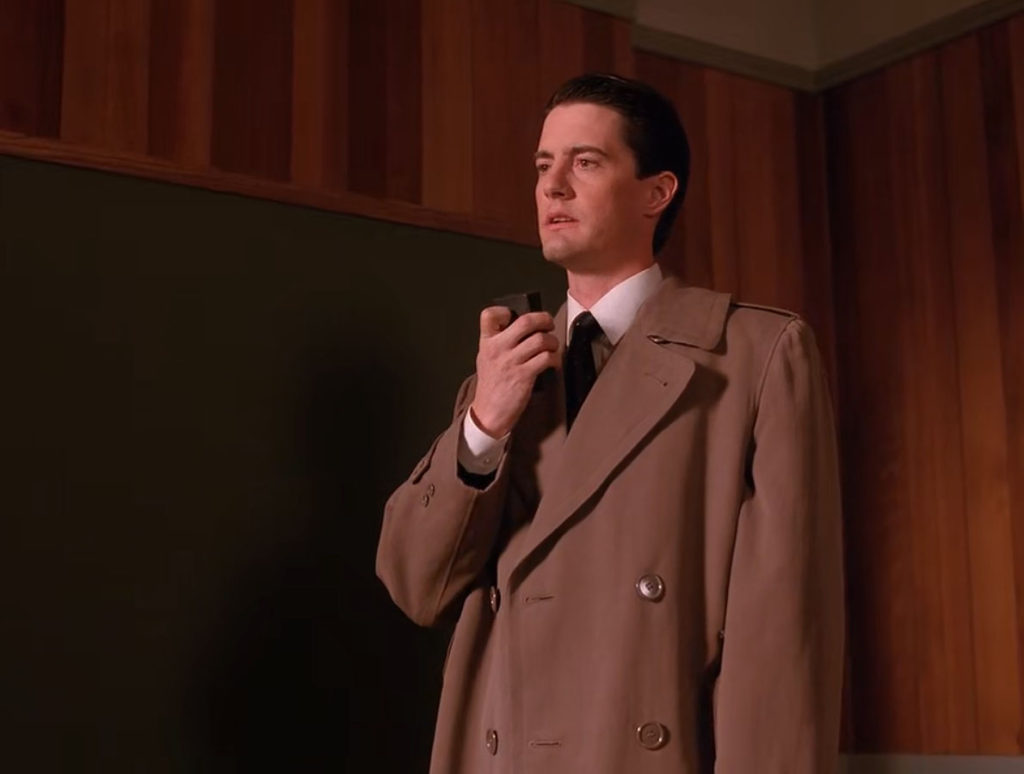

And I remember I had to ask or I asked David if I could use some of his original material of the dream in my show, and thank God he said yes, because it was my first scene and people were going to die on the spot, no matter how interesting Kyle’s dream is, you’re still sitting down.

Leads come from inside his own psyche and in this show, the psyche goes public. And the admission of Jungian power goes public. And I don’t know that that had been shown on television before. I mean, where where a is where Coop is actually taking his clues from inside his own psyche. That’s feels very David. And that felt very like a new world, a new dimension.

Once you got all the characters, and story and everything down, tone and sustaining strength of tones running along one another are the difficult. And then you, then that’s when it really gets fun. Because that’s when you have a couple of reins in your hand and you have to keep playing the reins.

I always worked on location. I had never worked on a set and we dreamed up the flying the curtains that Michael Ontkean could pull aside and the gurney could roll. And the gurney with her body on it was used as kind of a bridge between the good guys and the bad guy.

One of the other things that was so much fun about doing this show was David’s goony, David and Mark’s goony sense of humor and their willingness to go with the goony.

Miguel Ferrer, I mean, the whole set could barely keep a straight face when Miguel got the drill and would go [imitating drill sound]. I mean, it was very hard for everybody to keep it all together, including myself. But that’s perfect, because then everybody was very. Their lines are very serious. And you have the cadaver there. So you always have this anchor against [imitating drill sound].

It had to be shot very quickly. And, I mean, I’m just reliving the day, and I’m back on the set, and it was no more difficult, it’s certainly the most difficult day was the funeral. And although there was a little bit, there was quite a large cast and I was a little discouraged at having to pack the frame in order to get the scene in the autopsy.

I remember trying to use Miguel and Miguel’s shenanigans and the corpse to relieve that time driven necessity. You know, master medium shots in which you pack the frame full of characters just to get a certain amount of work done.

But I didn’t really understand when I was making it was how much it was a bildungsroman of Coop’s – what he was learning and that seems much more sophisticated than I had understood it to be when I was there.

I felt I had gotten a very juicy episode. I mean, I really felt I’d gotten at a plum, not only because of the funeral scene, but also because of the emotionalism. And I really appreciated being able to use all the single shots that I was able to use. Nobody, nobody slapped my hand for staying on Leland the entire for the first three quarters of that entire scene.

In retrospect, we had to cut in the the soap that he was watching but I think was as it was originally conceived it was just going to stay on Leland. And I think it gives the actors kind of an energizing, inward thrill to know that it’s going to be one take on them for a very significant part of the scene.

TWIN PEAKS – EPISODE 1.003 – ACT TWO COMMENTARY

I feel that they, you know, give a kind of gold that building of scene is going to be built out of one shots and two shots, so they can sustain and augment an emotion that ordinarily, certainly on television, they’re not invited to do.

I also remember getting the script only when I, I think I got it either the day I left or when I first got to L.A.. And so there was this incredible short learning curve that we went through to meet the characters and the sets and and the script. And the production manager on my segment was wonderful and was willing to work with me to map out all the shots. We obviously couldn’t do it with the DP, but but he and I did it together and it made all the difference so that when I got to the set, I could really work with the actors.

Now, we’re, watching the scene in which we meet Leo and placing the car in the scene was, of course, deliberate, because it, it connects with what he says with the car, but it’s also the use of red in particular I loved against all the Northern colors. I’m trying to remember if there was any blood of Laura Palmer in the pilot, when her body is found. I’m trying to remember if there was a little, a little bit of blood.

This scene with Dana and Don Davis, I remember it was one of my favorites to work on. And I remember thinking when I first studied this script, that what Don was saying with that, what David and Mark had intended of Don was that he was a stuffed shirt and representing the establishment essentially.

So when I tested that to David, and David said, “No, he’s a wise man.” When when the issue when when Don Davis, the colonel [sic] is, is known to be a sincere man, then Dana’s bad boy-ism is revealed as idealism at the funeral is much more moving.

To have them cheat up against each other, so to speak, in that father-son scene, and Dana, you know, playing with the flame. I mean, I got to really play with designing shots, and some of them I think are more forced than others. Some of them I did because it would mean only one lighting set up, and that would buy me more time to actually work with the actors.

In other words, simplicity I hope, and I’m not sure I can entirely reconstruct this, but I hope that the simplicity was an effort to minimize setups and to maximize working with their performance.

[Betty Briggs] is so isolated and the role of the women in Twin Peaks is so isolated. And they are so, they’re all, each of them so on their own.

When I got there, I just had to sponge, sponge together the atmosphere and from from everybody who would talk, talk to me. I feel very comfortable with women. And I feel that one of my roles as a director with women, and I actually feel this as one of my roles with a director with men, is to empower them. And to use that overused word.

So whenever there was a woman in the script, I enjoy making them flourish. And I think that some of the women felt an initial mistrust of me. And it went through my mind that many of the women, not having had a chance to work with women directors, had felt that they had to use their femininity to gain any autonomy with the director or gain, gain power with the director, and that they were a little panicked that since I was a woman, I know that they wouldn’t be able to seduce me that way.

What they would, I hope that they learned is that they were able to seduce me in another way, which was in with the power of their work, which they did. And when I watched the film again this morning, I was the women really are very isolated in Twin Peaks and hemmed in by violence.

They don’t seem to be, I’m thinking mostly of the Mädchen Amick character, they are a victimized by their devotion. They are victimized by needing the men, their men. And yet being banished from the earth but afraid of their men’s violence. So it’s to me that the truth of the film, one of them, to show, it was brave enough to show.

TWIN PEAKS – EPISODE 1.003 – ACT THREE COMMENTARY

I, I also see that there are that David and Mark are, I mean, some of the casting in some of the characters almost seem to be banal, and yet that seems to be part of the facade of the ideal American town that David was trying to create to unpack that a little bit.

You know, Kyle is a wholesome American boy. And Laura Palmer is a wholesome American girl. There’s something very, very American and nearly banal about how they are, what they feel like. And and I can’t help but think that that’s very much you needed for a David and Mark to play the the strange and violent against.

[Big Ed’s] catatonia at her madness is I regret as the director, I wish that I had asked him to forget her madness for some portion of the scene, so that when what you have as a touchstone how it had been for them, so that the grief of what he had lost his is more present.

Because this way you don’t really know whether how it whether it was good for them ever. Therefore you don’t have any I can’t history to his sadness.

Some of the sets, it seemed to me, were virgin. That is all the the the burden of all the shows wasn’t loaded on all of it by now, and it hadn’t become a hit by then. It hadn’t become a cliche yet. There were a lot of treasures that hadn’t been used. And that was the other good thing about coming someone at the beginning. You could, find corners that nobody had seen in sets, and you could define moments and define and, you know, bloom certain aspects of certain relationships.

We were handed a reel, I guess, of stock footage, which David had initiated on his shoot of the pilot, and you could go through it and and pick what you wanted to use. And because I was one of the first people coming in, a lot of the footage was still very fresh in terms of its symbolic, weight.

The wind in the pines, I remember, was very useful to me. This, funeral scene around the coffin was certainly my initiation by fire in sight line. If a character is looking a certain way, who or who are they looking at when you mount it in the editing room? I regret not having a more productive master shot. But that’s the toll I guess a very short, of short days.

I get quite drawn into it. I had, and I. I’m always looking at the mixture of sincerity and cruelty. And it seems to me that was, I think, whether it was intended or not, show is always walking that edge.

You know Dana’s “everybody knew she was in trouble” speech up against which seems very, brave. But his treatment of his father is also very cruel. So and that’s very human. But the the show seems to be constantly walking that line.

I think the slow motion works and especially works for the economy of, I mean, it’s very economical. But I can see that I need more material linking the close shots. The close is what I always love because, especially when you have very emotional material like this, you need to see what they’re feeling and thinking.

But, they’re like islands in the master. There’s no medium to link you, which is just a personal reflection of of crudeness. It’s not that I feel that one shouldn’t do that. It doesn’t. You can do anything you want, but it feels, it feels disorienting. It seems as though I always have to have my fun or otherwise I rebel.

TWIN PEAKS – EPISODE 1.003 – ACT FOUR COMMENTARY

This is the scene where I think everybody didn’t really know their lines. And I remember seeing let’s just turn on the camera here. The camera lifts up and, flies over the head of the two men at the bar and goes to the corner sit down. That was again, you can see me straining at being back in the diner where it’s two shot, two shot, two shot.

And I knew from Zelly and Me, David’s love of certain foods. And I knew that from Isabella too, and some of the funniest moments that I just remember personally. We had one reshoot of Zelly and Me. We needed a close up of David, and we got to the set on Long Island. We just all went out in a car and somebody had brought some corn muffins and some coffee for David, and I remember David, one of the funniest things was seeing David eat this corn muffin.

And he said, “T, this is going to take God knows how many cups of coffee to get down.” So I knew how much he loved his coffee and donuts. And it seems very him to me. And since I know Kyle seems so David to me all of that seemed to be like a very enjoy transparent and nourishing code.

And then going to this Hardy Boys, you know the the movement in and out of, from Jung to Hardy Boys and back. There’s a spin on it so you never can say, oh gee, this is getting too anything. Because the minute you think you know the territory you’re in it, it flips on you, which is what’s delicious.

I’m trying. I’m going back. If you have the camera on me. My eyes are rolling back to this set and it’s just the way it was. And it was tiny and and, you know, hard to shoot in but that was perfect. I mean, that just fed in what we had to do. But you see this is much too static.

I remember feeling at the end of this show that this was not, there was so much energy expended just to overcome the constraints of time that I remember feeling that you really, you couldn’t make your life spinning this kind of energy on this kind of material? It was kind of a when it had to be a one-time thing, because after a while, you just wouldn’t have had the heart to try and explode the constraint of time and money.

I mean, it just took too much from too many people and it was too, it couldn’t do what it was doing unless it tried to sustain the highest level. If you let it go down, then it would become banal in a way that wouldn’t work for the show? And it was clear that you got to get the kind of quality of script writing wasn’t and the quality of this story and the balance between those tones that you were wasn’t going to be able to be maintained for a very long.

Joan Chen and Michael Ontkean in their scene. There doesn’t feel anything particularly predatory, although having said that, the Joan Chen character does seem to, the Sheriff does seem to be a sitting duck for her character. Watching the scene myself and having forgotten – this is funny – having forgotten what is going to happen and some piece of the backstory, I feel that she is setting up Michael Ontkean up, that she is much more powerful than he is and is really weaving her web to later make use of the Sheriff.

Which I don’t remember being conscious of at the time it was shot but I do like the fact that Michael is seen as the heavy in all the other scenes. And here he is lighter weight as a character than her character. In other words, he’s less powerful. He’s very vulnerable to her and in the other scenes, he is handing down the message from on high with the other characters in Twin Peaks.

So I feel that David and Mark certainly knew about the changing of powers and how that would keep the show from being banal.

But I felt when things started unraveling, I mean I felt they started to unravel into its own complexity in the second season. In the first season, the complexity seemed tantalizing. And in the second season, the complexity seemed for its own sake. It seemed to have gotten mannerist after awhile.

I got the script either the day before I left to come out to L.A. or the day I got there. And I remember knowing that we only had seven days to shoot, I don’t know I’m making up, 49 pages. And so, I drew out, did a storyboard for all the shots and I also went over them with Toni Morgan who was the editor.

I then called all the actors because I knew needed to at least meet with them for SAG [Screen Actor’s Guild] reasons and for the budget reasons, there was no, there was no money for rehearsal. So I just had to call them and say, “Do you want to have coffee?”

And some of them wanted to meet with me and get together. I remember Peggy Lipton we met first at her house and I remember going, I remember loving working with her because I think at first she was quite frightened of me. But then as we got working together, she realized that she could let go, she could trust me. And for a director, that’s one of the greatest feelings is when an actor surrenders to you so that you can really work together.

And Michael Ontkean I remember said, “I made 27 feature films or 47 feature films and I don’t really need to rehearse with you.” And I remember saying, “Will you at least have coffee with me so that you can explain to me your character because it will make me a better director of your piece?” And I was very, I loved working with Michael. At the end, I had the great reward of him coming to me while I was shooting, there were three sets going at the same time and we were completing the cemetery, the funeral scene, and there was Michael saying, “Do you think you can help me with my close up?”

So really when you got to the family, the ongoing family that was working all of the time, you did have to prove yourself in whatever way to each of the layers of the staff. Because you could tell everyone was thinking, “Why was this person brought it? What do they have to offer us?” And so you had to prove yourself to every single person you ended up working with. And to some extent, that was fun and part of what made it so rewarding at the end.

Because once you got people on your side, so to speak, then they would start bringing you their treasures. And whether that was the costume director or Richard Hoover or the actors. And sometimes even, I remember Harley [Peyton] would you know rewrite little lines for me that didn’t feel quite right.

It was lots of fun to come into the making of Twin Peaks before anybody had any idea that it was going to seize the country’s imagination the way it did. You know, we were scrapping and scrounging, never having enough money or time, but that gave us an incredible freedom that we could do kinds of shots and kinds of editing that when the show got more, much higher national profile, that was no longer possible.

And that seems natural that it was completely unknown when we went to work on it. We had no self-consciousness about working on it. We were just there because we love David’s work and we were given a chance to do things that nobody else was going to give us that same chance.

But after it became so popular and after we learned who killed Laura Palmer, it seemed to me unimaginable that it could sustain in itself without David and Mark creating an MacGuffin that was as compelling as the death of Laura Palmer and it had been so power that it would be completely astonishing that they could do that again.

Discover more from TWIN PEAKS BLOG

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.