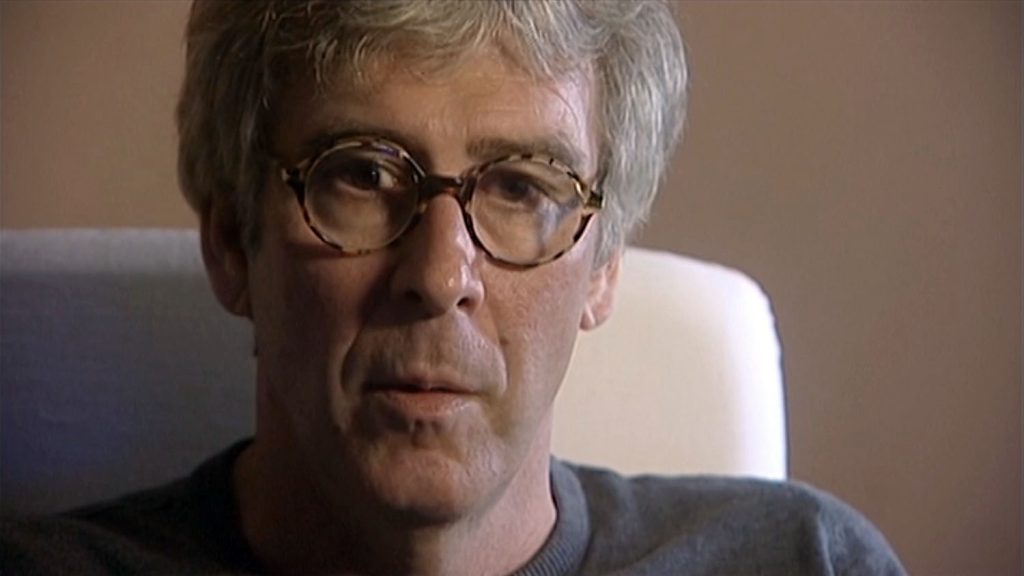

The Twin Peaks – The First Season Special Edition DVD Set was released in December 2001 by Artisan Home Entertainment which included audio commentaries by crew members who worked on the show were included. The first episode had insight from Director Duwayne Dunham. For the David Lynch-directed episode 1.002, Director of Photography (or Cinematographer) Frank Byers shared technical insight into how he lit and shot the 29 episodes from the first two seasons of David Lynch and Mark Frost’s wonderful and strange show.

TWIN PEAKS EPISODE 1.002 AUDIO COMMENTARY FROM FRANK BYERS

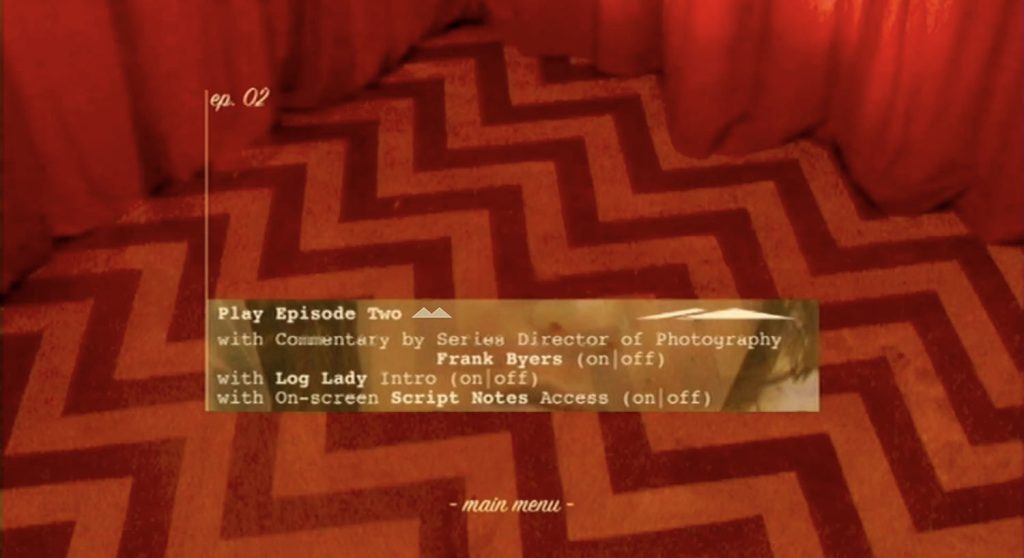

The audio commentary from Frank Byers is found under the “Episode Features” tab after selecting “Ep. 2” from the main DVD menu.

[Voiceover from Michael J. Anderson plays over the “Previously on Twin Peaks” montage] Cinematographer Frank Byers supplies commentary on episode two. Frank Byers.

[Frank Byers] My name is Frank Byers. I was the director of photography on episodes one through 29.

When I first got the job for the series, Greg Feinberg and David Lynch asked me to go view the pilot, which was being, previewed for the network, I believe in film and a film screening at the I believe the the venue was a Director’s Guild theater, which is a wonderful theater. They may have given me the script. I don’t quite remember. They may have said, “Here, read the script first.”

But, I remember going in pretty blind. And so I went in totally as an audience member. I was not there to, make any decisions or I wanted to take it in, as everybody else did. And I was just blown away, just shocked at what, one the content was and two, I just kept saying to myself, “This is going to be on television?”

You know, I just felt that this was some new ground being taken and certainly, content wise. And, I was excited. I thought that, because Greg had sort of explained what what was happening briefly because we had met only a few times concerning this – I had worked with Greg before – in terms of what the overall story was and where it was going.

He said, “Look at the pilot. This is what we’ve come up with, and we’re making a series based on this, murder.”

And so I guess where the best way I could put it, the murder of based on a young girl getting killed in a small, northwestern town. And that’s about all I knew about it. And I saw the pilot, and I said, you know, this is an interesting concept for a television show, and I’m not quite sure that anybody knew where we were going with it.

I mean, obviously the four principal people involved with writing the script – David Lynch, Mark Frost, Harley Peyton and Bob Engles – knew where it was going. Harley Peyton, who I think is a pretty vital force in certainly the overall direction of Twin Peaks and, later on, I know became a even stronger force. I mean, maybe not quite so much in the seven episodes. It may have been laid out by David and Mark more after the, the arrest of Leland in episode whatever, 13 or 14, I don’t remember. I think it became a lot more Harley’s.

This first seven episodes, we work 16 hours a day, and, I worked every shot. I operated this, this was nonunion here. This first seven episodes, I operated as well, so I operated I was there, I was there every shot, no matter what. I had to be there.

So by the time that first seven episodes were over, there wasn’t much, much left of me. It was physically and mentally pretty hard. Got easier in the next 22 because one and I had an operator and two, we were still experimenting in the first seven episodes.

So we, I believe that the script, length was 65 pages, and we’d wind up with, 15 to 20 minute, this is what I heard anyway, 15 to 20. I’m sure it wasn’t quite that much, but of extra minutes of footage that there wasn’t time to put in the show. And so by the time we got to the second, season, the scripts had gone down to 45 pages, and the were there was more time to to shoot because we weren’t shooting 20 additional minutes of footage or whatever that might be per show.

So, you know, we honed it down as to what, the shooting day down to basically the normal 12 hours by the time a second season had come along.

My feeling was, in more conversations with David, but my feeling always was and about what to do with the lensing or how to approach the show itself. And I noticed that David seemed to like wider angle lenses for that particular look. So the show that I kept looking at and honestly, was my one springboard for the first seven episodes was Touch of Evil, certainly in the lensing.

And if you look at Touch of Evil, it’s all wide angle lenses, even the close ups. I just kept looking at that for the lighting, which was a black and white picture, and I wanted to take, translate that lighting style to a softer lighting style, which I felt was more appropriate for Twin Peaks, given the environment of the northwest, which is usually an overcast non-direct light.

And also David likes things to be dark. He likes things to be a little sketchy sometimes. And, I had to keep that in mind too, which I felt also Touch of Evil translated very strongly.

I remember that shot. It’s on Malibu Canyon somewhere. There’s a little lake. We waited to the very end of the day, and, I think I was shooting at f1.4 which means the lens was wide open. There wasn’t much light left. You look at a show set from episode one and varied very, very little.

Certainly the concept of the look varied not at all. How to achieve that look sometimes was worked on for the better. Yes. And, one thing I specifically remember was him telling me, David Lynch, that he wanted a warm and comfortable look on the outside so the inside could be turbulent or things happening on the inside. Meaning the story happened within this veneer of warmth and comfort.

He would say, “While I’m trying to make a mood here.” And, that look had to do with what David said was the mood, and the mood was very important to me.

I did very little lighting from the from the ceiling, all the sets I could certainly through the first year, I did almost everything from the floor. I didn’t I don’t like, particularly the look of, I think it’s unnatural and only had only do it from set walls or whatever if I want to add a backlight or, separation or whatever, or just this is no other place to light from because we’re seeing more of the room. But whenever I could do so, I lit from the floor.

This is a practical set, which was too small. This is not, this is not built on a stage. This was, I don’t remember where. I don’t remember when, but it’s not on a stage. It was really tough to light in here. I don’t remember where it was, but I do believe that we walked outside and shot the night exterior. This is the same location, so I imagine it’s somewhere in Malibu or Malibu Canyon.

I remember episode two being really small. The room really small and not being able to to quite, deal with it, like I wanted to. It was a difficult location for me. I remember a different location for, the stuff was Jacques Renault. Our different room of it anyway.

But I also remember shooting two different directors out there at one time because we, we we went to shoot location specific. In other words, we knew we were going to be out at this location rather than return to it for a half day’s work, which was impossible. We did two days, two different episodes one day in that location. That’s not unusual for television at all, but, you know, you go to some location, you know, is not going to happen again. And, may not have a full day’s work there on both episodes. So you do, you know, one scene there for episode whatever and another scene from the next episode.

I’m pretty sure that’s what we did in that One Eyed Jacks location, and we never went out to it again for the following up. The the next season, we built Blackie’s office on stage. And I think that’s all you ever see of the One Eyed Jacks again.

Coming from David on an edict from the pilot, that we decided to warm the the picture up, with the use of coral filters. And, the lab was able to to do a good job. We had film dailies, which I think even ten years ago was unusual. And for me, it was fabulous. It was a really the way to go to to take a look at the daily work and judge it, especially with the coral filters, because if if I had gotten just, which I think was standard at the time and in a way still is, a half-inch copy of the dailies, it would be useless to me and run through on a slop dub. It would have been totally useless.

So it was it was important that we saw the picture on film and exactly like we. So we could evaluate exactly what we needed to know. And I can remember to this day that I would print, which is a compliment to my gaffer actually, we would print every day, would come back the same light – 42. I think it was 42, 38, 42 and I played with under exposure and all the time. And so for my gaffer to be that precise every day, knowing exactly where the, you know, taking the reading so precisely and whatever, that’s a, the lab would compliment me all the time on that. And I was that was something I was very proud of.

And the dailies were very consistent, no matter where we were, whether it was outside or whatever. So that was, the lab did a really fabulous job on that. And it was I think we shot a million feet of film between the whole 29 episodes. I mean, there’s a lot of film. We shot a lot every day.

You also had to take into consideration that we shot one episode in seven days. It’s a lot of work. And, the constraints of your time and the time you can take to accomplish what you would like to accomplish are pushed to the max length in a seven day episode.

But I was happy with what what we did. I think, that the general consensus among the crew was of great interest. I would notice, that while we were rehearsing a particular shot or whatever, everybody was watching and nobody knew what the story was because the script and electricians never got the got the script. And, they were really interested in what was going on that was, made it a, really concentrated effort. I thought from everybody during that first seven episodes.

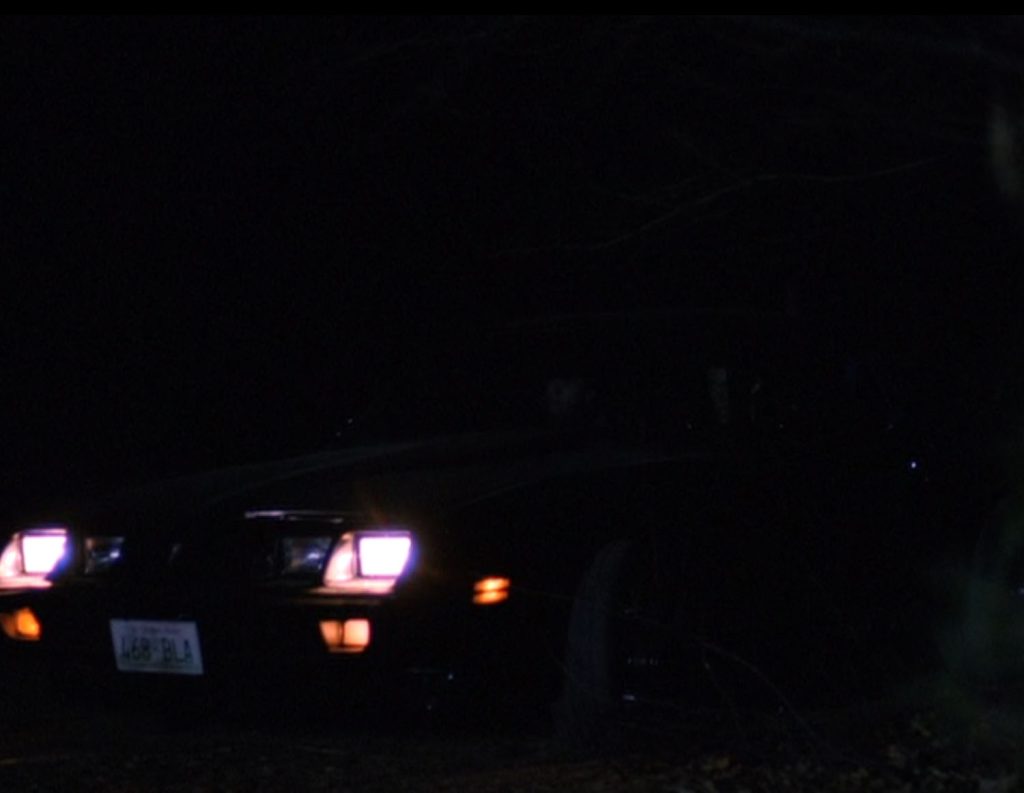

You know, we got out there to do this night exterior and there’s certain physical aspects of the film, you know, and what you see by your eye is not necessarily what you get on film. It has to do with how you expose and what you’re filming. In this particular instance, on episode two in the woods, it’s green, which green soaks up light like a sponge. So often times. you’ve got to over light that green a little bit and it will still look dark.

There’s a large, source backed way up. If I remember, I bounced a 12k HMI [light] off a griffon, so it was really soft. And, that’s just flashlight only in that particular scene.

See how far down the blue light is here when the flashlights don’t hit? But I can still see some detail in the trees in the back, surprisingly.

Originally, I had that a half stop under key underexposed that I was going to expose this that, I think the zoom I had was f2.5. And, it was a possibility that we would have to zoom or, or make some type of small adjustment here, if I’m remembering right. Anyhow, I usually try to light up to a, a f2.3 or f2.5. So had the possibility of using the zoom had I need to do.

But we were on primes [lenses] here and, I think I did a half stopped and David said, “No, no, this is unnatural. It’s too bright. You’ve got to take it down.”

I said, “Well, David, and I’m underexposed it two-thirds half, two-thirds of a stop.”

“Yeah, but it doesn’t look good by eye.” [said David]. And, you know, I didn’t feel that I was going to win any battle of explaining to him well, exposure wise, it’s actually pretty far down. I want it to look like to my eye, good. And, so I knocked it down, I think I was working at four foot candle, which is pretty far down the line there.

But I underrated the film here. I rated a 500 ASA at 320, so it was always overexposing to get a thicker negative anyway. That’s why I printed 42, 38, 42 on a lab that I think the middle light was 36. So I wanted a strong negative 1) because I knew that in the telecine [ed. note – transferring film into video] we would be better off because I had good detail on the shadows. I wanted to save the shadow detail, so I overexposed a little bit. Not much.

So I knew I had some room there. I pulled the coral. There’s another half stop. And I shot at f1.4. I got, I lit it to f1.4, so that now that blue light, I still think it wound up being a stop and a half down, but it was, not quite as far as what David thought it might be, but it looked more natural by ISO. There we go.

But I think that, Yeah, it’s, you know, shooting something at f1.4 to f1.2 even some of the lenses were that it may not have wound up being anything more than a stop, which at nighttime, it’s often what you do anyway. And, the flashlights were, oh, God, they might have, they were probably at the brightest 16, you know. So, we’re talking about a contrast range that’s pretty strong here.

So that when he puts it under his chin, he was definitely, you know, three stops over or whatever in the hottest point. But we use that, you know, it’s another place where we just stretched it, you know, how far can we go? How far can we make the contrast go?

You know, because edicts on most television shows at the time was flatten it, you know, flatten the hell out of it. And, it’ll translate better when you, when you transmit, you know. But, we didn’t we, we pushed as far as we could go. And that’s one scene. I mean, even I, I have to say that I had not done that before. I had not gone that far before.

TWIN PEAKS – EPISODE 1.002 – ACT TWO COMMENTARY

I was interested in looking at the dailies for the next day because I didn’t know. I honestly didn’t know. You know, did we go too far? Did I go too dark? Did I make too much contrast? But, by eye, it looked great. I mean, by eye it look really interesting and, you know, so then you just go with your instinct and say, okay, I’m going to go with it. And, you know, I knew that I was shooting so wide open that I was going to get, that I had an image, you know, regardless of what was underexposed and what wasn’t. I certainly had enough light to make it work.

And certainly dramatically, what we decided to do with the light work in my mind, like a charm. I mean, it really gives it an energy and, mood that, we coordinated in order to get in order to make sure that we visually we had some type of a story being told with the light.

You know, it’s not just stick the light in his face on who’s ever talking. There was a lot more going on in that particular scene as far as the lighting goes, and as far as where people were, how they were illuminated and what they were saying when they were illuminated. So we we really worked on that.

I don’t remember doing two cameras ever, and which is, standard Modus Operandi in a lot of television shows. We were one camera, one camera only. That was great. Never had to compromise the lighting or especially, and I’m going to get back to this again was, the way the women looked. Never had to compromise that by having to shoot two cameras.

First seven episodes also were shot on the Arriflex system with Zeiss lenses. I think there were Zeiss Super Speeds, which to my particular taste are a little too contrasty and a little too snappy as opposed to the especially the newer Panavision system at the time, which was the Primo Prime lenses.

But it was honestly my choice. I’ve been working Arriflex at that time, and it was also financial choice, but anyhow, that was what we decided. So I filtered the the Zeiss lenses with a filter combo tha was a low contrast one and a black net number two, for a lot of stuff. And I thought it gave a really nice look to the show.

I never wanted to pre light anything. I never wanted to say, okay, “We’re in, okay, we’re back in the diner, formula 144, let’s go.” I always tried to take it, scene by scene, shot by shot, with some success and some failure. I think on my part being that, either I couldn’t think of anything different to do or I didn’t have time to do it.

Mainly I didn’t have time to do it, but, I felt in the diner, I didn’t want to just over it, you know, the the way most people think about a diner is overhead light and whatever. I didn’t particularly use that all the time. I mean, I tried to underexposed the front light, sometimes and maybe rim light the people a little bit more.

I used different concepts in the diner all the time. I mean, I think you can go to certainly the last 22 episodes and things drastically changed. I try to throw away what I had done there before and, you know, start new. Depending on what the scene was. I didn’t always think fast enough to make that work. Sometimes it was just get the job done, but, I tried.

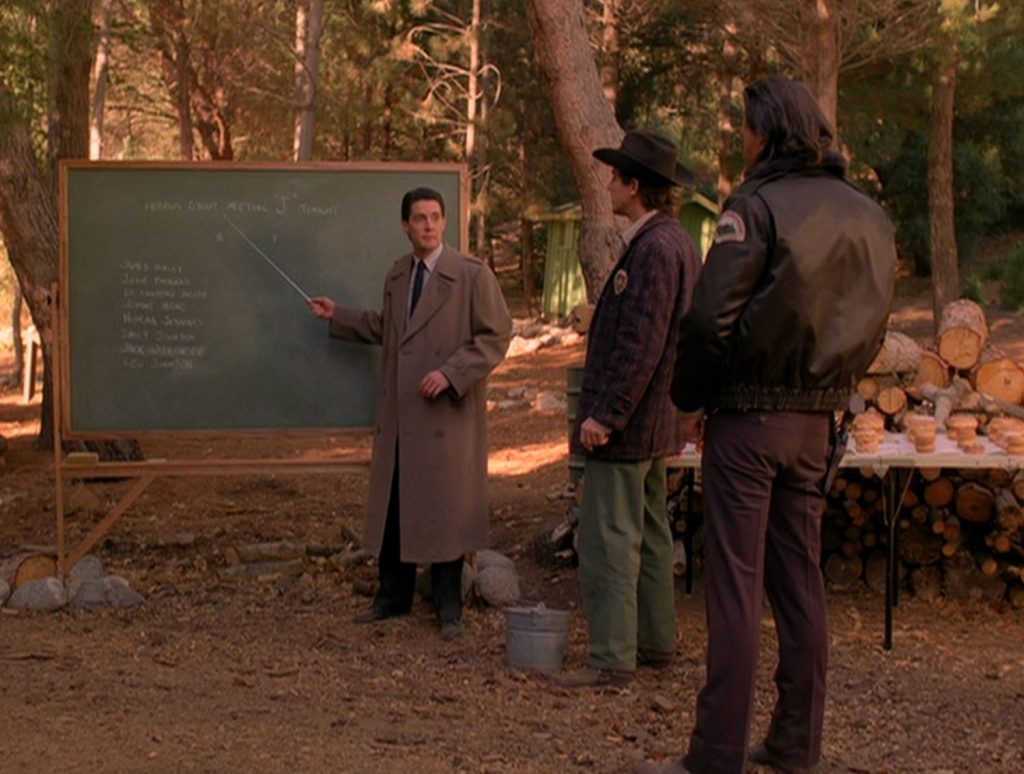

To make it look like the Northwest, we tried as much as we could, and we, I honestly just think that we got lucky. Like this particular scene from episode two where he gathers the the troops up to sort of recap what he has come up with in terms of the suspects.

There’s bright sun happening in the background there, which we always try to avoid. We always wanted it as overcast as possible. And honestly, and this is just pure luck most of the time we got that. I don’t know why. We just got lucky. You know, once in a while, there’s some sun, something happening in direct sun. But here, at least the characters are in the overpowered, overcast part of the woods here.

And I remember coming in this day, and it was like bright sun on this particular part of the woods here. And by the time we shot it, it wasn’t. So, we got lucky. Here was also a very long scene, so we shot it probably a few hours.

You know what? I think that we shot this scene and then went into the night exterior, and I had some kind of, if I remember, I don’t know how I can remember that, but I believe that’s what we did.

I always felt, how far could I take this? And still, wind up? I’m still be able to translate it to television. I remember when The Godfather came out. I guess this was a little bit after those days, but the original concept of, well, the general consensus at that point was it’ll never make it to you’ll never be able to look at it on television.

And honestly, that could have been true at that particular time. He was shooting for a theatrical experience for the audience, and that’s what he went for. And he pushed it, you know, to what he felt was an interesting avenue. And, but many, you know, people said, well, you’ll never be able to see it on television.

And I bet I don’t really quite remember, but I bet that the first few times that it came on television, it was the Jack, the the signal of so far that it looked it didn’t look anything like the original. But if you look at the remastered Godfather that Gordon Willis did, I believe, it looks fabulous and it looks great.

So, I felt we were dealing with those concepts at that point. And, the reasoning for that, I believe, had a lot to do with one David Lynch. I mean, this was not your normal television director for the sensibilities of television. This was of his own sensibility, his own directions and edicts, whatever they were, his. And I don’t believe they were polluted or, swayed by, oh, this can’t be on television or you can’t do this.

I think that that was thrown out the window, and I believe also for myself that, the experience of working in, because I had done all different stuff up to this point, I had done some features, I had done some television shows, and I had spent a, a good time doing, working in the rock video world. And, that experience enabled myself to push a little further because I knew it could wind up on television.

I knew that heavy contrast was going to work because I’d seen it. I didn’t feel I had to resort to the formula that had been used on television. I guess that’s in a nutshell, how I can explain it. And coming from David, I realized that I was free to take that avenue that nobody was going to be on my back about, about under exposure or overexposure or, I was never approached. This lady needs this light. This lady needs this light.

Although from my own way of thinking about it, that was always constantly on my mind. I feel that women should always look really, really good. It was something I worked on very hard on Twin Peaks. I felt that every woman had to look as spectacular or as as nice as I could get them to look without resorting to that the light over the back of the camera through a silk look. It was a different way that I approached it.

I felt I never threw away a shot in particular with that particular edict in mind. I never I never said, okay, I got five minutes to light this lady. I wouldn’t do it. I said, we’re going to do this until she looks like she’s supposed to look, and that’s it, regardless of who’s going to give me trouble.

And, you know, I mean, the production managers are always looking at the clock, and that’s their job. But, that would get me into trouble. But that’s what I did. And I never, never threw away one of their close ups in all 29 episodes.

TWIN PEAKS – EPISODE 1.002 – ACT THREE COMMENTARY

That’s for series TV. That’s the hardest thing to do is to keep running a thread through what you do every day. And not get beaten up by the schedule or the location or whatever that might be. So, the way that I approach the light on all the women throughout the show, they always had a very soft type of key. I mean, they were not hard lit in any way, and I would often underexposed the front light depending on what the scene was and where they were in a particular building or whatever underexposed it, a star or whatever that might be.

But I always tried to get a really creamy look, pushing the light source and the close ups as close as I could to their faces so it would wrap around and fill.

If you move the light, a source, a soft source close to the face, it starts to react in a in a different way than if you threw a hard light from far away. And it starts to make to me, makes the skin glow. And that’s what I went for. And all the women all the way through, but especially the the young, the young girls, I wanted them to be real appealing and once again have that veneer of innocence and and comfort and beauty, you know, but, and then underneath, we all know what was going on, or we found out what was going on. But I wanted that, real creamy flesh tone and glamor look, without going, without going too far.

What I used to do in the close ups is I take a show card and I’d cove it. And I take, whatever light I don’t remember, and I’d bounce it into the coals. And then I put a piece of diffusion between the coals and the subject as close as I could, just out of frame, as heavy as I could get away with tracing paper, usually. So it would be like a china ball.

I always tried to put a rim light on them, but really low, so you would always see the line of the face, outline, you know, without having it. It’s sort of just a real thin line of I tried to, I get it as close as I could to the frame line and I, you know, I felt that that look really nice on all the ladies.

I remember feeling feeling that we were doing something a little bit different when we shot this, this dance that Sherilyn does. We played the track on the set, and it’s the first time I heard any of Mr. Badalamenti music other than the Twin Peaks theme, and this one struck me as something that I said that I really noticed, because we played it over and over on the on the set that day so she could dance to it got.

And it’s a very unusual track and I could see the guys in the background going like this [snapping fingers]. It’s really catchy and, unusual. I mean, you don’t hear that combination of instruments, for one thing. I mean, it’s a lot of synthesized things going on there, but used in a very good way. Upright bass, which, played very well and recorded very well.

You know, if we could a very hot I think it’s almost like, You remember the older albums by Serge Gainsbourg? It sounds almost like that with bas, and guitar and, it’s a jazz-oriented score. It’s not a rock-oriented score. It’s actually based, I think, in jazz, but it’s not, the substitutions of the chords are not so complicated that you can’t follow it. It’s almost like the, you’re caught your chord immediately just by the power of it. You can’t immediately by the beat of it.

The editing style and the coverage of Twin Peaks was much more conducive to what David always described as the mood, which I know was central, and how he felt, I believe, and how he feels about all pieces.

But, certainly, rather than do this all terribly close up, which at that time was most television shows, there were a lot more wide shots. And, my feeling was that, that was the mood you felt. You didn’t feel confined or whatever, to some idiotic dialog that, you know, might have been going on in other television shows.

This felt like you were really trying to trying to catch the audience. And, I believe that that worked. And this is all wider, very much related to Touch of Evil in the use of wide lenses. Not only in wide shots, but in closeups as well. I think that it looks like Miguel’s closeup is done on 24 millimeter [lens] or even under. It could have been a 17 [mm lens]

But this concept goes throughout the first seven episodes strongly And David went right for it. I mean, he really, he really, I knew from speaking to him that he was a wide lens type. So certainly went right for it.

For a cinematographer, that was much more, appealing in order to to do those wide shots and actually see them wind up on on the finished product. You know, most of the time you would at that point in time, you do a, a crane shot or a dolly shot, and the editors would cut out of it before it was done.Not on this show. And that was a real plus. And I felt really worked and I hope taught the rest of the television world a lesson. Whether they picked it up or not, I couldn’t tell you, but, I honestly feel that television got better because of our show.

I remember another episode that he did, I don’t remember which one, but it was in the second season, where we had a scene in the police station in the interrogation room. Must have been trying to find the lodge, because it was all these little doodads hanging around it were clues.

Anyhow, David rehearsed it for a long time. There was a scene for a long time, and, I well, he was the boss. He could get away with that. So, we rehearsed for a while, and he would only rehearse with just the actors at first, nobody else. So they call me back in and he goes, okay, we’re here.

Meaning a 14 millimeter lens on a wide, and he stage it so the actors would come to the lens in a way, which was, I thought, brilliant. It was a really interesting way to deal with this specific scene that had a lot of information to it and could have been just exactly that, just showing information or giving the audience detail. He made it more than that. He made it. He put a mood to it. And that was real interesting way.

But anyhow, he says, I want to be here, meaning this is 14 millimeter lens, which, like I said, he staged people to. And then I want and I go, what’s the coverage? Well, then we got this on Kyle, which is a tight, tight closeup of Kyle.

And I believe we only covered a few lines of dialog out of that closeup. So essentially the scene which was at least two pages long played in that master and, people walking in, walking to – it was staged brilliantly, I thought – but when we said that and then we’re here on Kyle, I was like, okay. And, you know, another day I learned something.

David tends to park the camera a little more than I think some of the other directors would have done. There were never any flashy. We never, I don’t believe, forced a move on a scene that didn’t, that shouldn’t need it. You know, you do dolly shots or whatever, but, it was never forced upon the on the material, which looking at some pictures nowadays, certainly some action pictures, which, you know, you want the energy or whatever. But I always feel that sometimes that those moves are forced onto scenes that they shouldn’t be there.

There’s no reason to go through 60 when you’re trying to, you know, imagine let’s let’s take Last Tango in Paris, which is always been another big influence on my work. Anyway, imagine doing a 360 degree move on Marlon Brando scene saying the big speech to Maria Schneider, you know, one of the big speeches. Why do it? And what’s the move going to do for you?

So that’s what I felt. We moved when we had to stop that. We didn’t move. We did move. And, I think later in the other episodes, we tried to we moved a little bit more, but certainly in the first seven it was a little more static. And I believe that that’s more David Lynch’s style.

The sets by Richard Hoover were fabulous. Now, looking back here, they were really great. And Richard did an unbelievable job. One little technical note, I mean this is we certainly shot Twin Peaks on a warehouse in Van Nuys. It was not a stage not a real stage, so we had no permanence, no catwalks, no, very little rigging. And also the budget precluded that we had to move lights from one set to another all the time. We didn’t have the amount, we didn’t … there were a lot of sets for one thing. But we couldn’t leave any lights, because of financial reasons really, at one set all the time.

I mean the the police station for instance wasn’t ringed with 10Ks that were just left there. We had to move them from wherever we were working before and go re-rig it. And there were two two warehouses back-to-back, I don’t remember. The diner was on one, and it may have been nothing, this was a smaller stage, it may have been nothing else on that particular set the first season. The second season, somehow we put the Roadhouse in there, which was way too big for that particular so I had no overheads over the Roadhouse. It made it difficult.

TWIN PEAKS – EPISODE 1.002 – ACT FOUR COMMENTARY

And then the other set the other stage we had the police station, the hotel, the corridors and Cooper’s room, which were connected physically. There were no, it was totally one set. I mean the dining room was connected to the hallways which was connected to Cooper’s room which was connected to the I think the elevator section came in later I don’t remember. But it was not you know the Cooper’s room on one stage and dining room and the other. It was one set was all connected, which was really good

Post production was done on film and cut on film but once that cut was achieved the negative had to be conformed and then telecine as a whole episode of cut negative. And the post-production work, and the telecine work, final color correction was done at Encore Video in Hollywood by a colorist named Drew Marsh, who I thought immediately understood what we were trying to go for and I felt was a big help in achieving the look of the final product in terms of consistency in the transfer and translating what we had on film to video tape.

He understood that it was not a particularly bright show that we were going for some darkness in there and I don’t know he looked at the print the work print at all. Obviously, he would only have access to the negative, that’s what he was doing color correction off of. Sometimes colorist who are doing a feature or something would go and look at the final answer print so they know where what direction they’re going in. I don’t know if he ever had time to do that.

There was a work print, a cut work print, so he could have done that I don’t know if he did. But anyhow he immediately I think knew what we were going for you understood what we were trying to do it with the warmth or whatever and I was very happy with what he had come up with when I first went in to look at the some of the final color correction.

This particular scene here, I believe, was shot during the pilot. I’d almost swear it because Laura looks a little different than what I remember her looking when I met her.

We shot the scene, this location again, for the second season we shot in reverse and [Michael J. Anderson] learned the dialogue in reverse, so when you played it back it’s sort of sounds normal. And he walked backwards and whatever. It was a way to go, something I hadn’t done before.

Held up in post until it went on the air, not held up, but I mean they were they had to cut and they’re cutting film now they’re not cutting videotape if I remember, conform, telecine, then color correct and then music and whatever there might be.

So the first seven episodes we were done by the time they even aired. We had completed all the episodes. But into the second season, we were shooting whatever episode that might be while, you know, three episodes previously was on the air. And I think that got down to even two episodes we were ahead. It’s a little tight not so much in shooting but in story. Because I know those scripts were being worked on right up to the end

Once the first seven episodes came out and we came back, it was a downtime of not too long I think we finished around Christmas time from the first seven episodes and that July or June maybe went back to start the next season, episode 8 (2.001) through 29 (2.022). And I think the first episode aired in March or April, so by the time we came back to start the next season, 1) the story points I believe they knew obviously they were they had gotten picked up fairly close into it. So they started writing storyline to do the next 29 episodes [sic]

Well there was such a reaction to the show and what was going to happen or memorabilia around it or whatever, that people started to go through the trash cans up at on near the stage on Van Nuys Boulevard to see if they could find any discarded script pages or any information about who killed Laura Palmer.

It was it was quite strange and to the degree that the scripts weren’t let out it, it hurt production because the scripts were let out until almost the day we were ready to shoot them. And as far as dialogue goes, I mean they would tell the technical people okay what we have a scene out in this location or that location. But we wouldn’t know what it was until basically we started shooting. It only lasted a few weeks in that mode but it did happen.

I’m proud of that show a lot. I’m very proud to this day, you know 10 years later for whatever it’s worth to me now. But I’m proud of what we did on that show and I really feel you know and this is, without tooting my own horn too much, that there were not that many shows that moved the way people think about television visually and I feel this was one of them.

Miami Vice, NYPD Blue and this, and you know there’s others like Hill Street Blues. But as far as the way you think about how cinematography is on television, I hope that this had a effect on what went down afterwards I feel it did and I certainly feel Miami Vice did. I mean things were never the same after that.

I feel it people felt differently about what could be on television visually and what the audience, not only would take in, but begin to expect. Because I feel now that you look at series television now, it looks a lot better than it did 10 years ago. A lot more is asked of you being a cinematographer on television nowadays and the schedules are a lot longer.

Discover more from TWIN PEAKS BLOG

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.